The presidential election of 1968 was one of the most chaotic in American history.

As a sitting president, President Lyndon Johnson was the front-runner for the Democratic nomination. However, growing opposition to the war in Vietnam, unrest on college campuses, and urban rioting made him vulnerable. With the end of the Vietnam War as his central issue, Minnesota’s Democratic Senator Eugene J. McCarthy announced his candidacy in November 1967. He mobilized hundreds of student volunteers, who went "clean for Gene," cutting their hair and campaigning for him in New Hampshire. McCarthy won 42 percent of the vote in March 1968 and, more importantly, twenty of the twenty-four delegates. His shocking success motivated Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York to enter the race for the Democratic nomination shortly thereafter. With approval ratings at their lowest as antiwar protests surged, Johnson announced in April 1968 that he was not running for reelection.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey then entered the race, but it was too late to run in the primaries. His only path to nomination was to win delegate support at the nominating convention in Chicago that summer. In the meantime, Kennedy quickly gained immense popularity in the race, and was, after winning California, within reach of securing the Democratic nomination. His assassination by Sirhan Sirhan, an Arab nationalist angry about Kennedy's support of Israel, cut everything short. His death, just a few months after Martin Luther king Jr.’s assassination, increased the sense of fear and instability in the country.

Many Democrats turned to the seasoned Humphrey, who by late August controlled the majority of delegates at the Democratic Convention in Chicago. Humphrey had been a supporter of Johnson’s Vietnam policies and thousand demonstrators descended on Chicago with one common goal: pressuring delegates to end the war in Vietnam and change the political system. Amid oppressively hot and humid weather, conditions in Chicago were ripe for a disaster: air conditioning, elevators, and phones were operating erratically at the convention; taxis were on strike; the National Guard had been mobilized and ordered to shoot to kill, if necessary. Chaos ensued both outside in the convention hall, where protestors were clubbed to the ground by the Chicago police, and inside, where the proceedings were at times out of control with shouting matches between delegates.

In the end, Humphrey received the nomination from an embattled party and choose Edmund Muskie as his running mate. But the damages were long lasting: many lost faith in politicians, in the political system, in the country, and in its institutions. Supporters of McCarthy and McGovern, who had rallied Kennedy's supporters around him, were left with a sense that the bosses, not the people who voted in the primaries, decided who the nominee should be. The discussion about ‘superdelegates” who have the final say in elections continues to this day. In the wake of the convention, the Democratic National Committee set up a McGovern Commission that put forth guidelines for the selection of delegates. They opened the party’s deliberations to more young people, to African Americans, and to women.

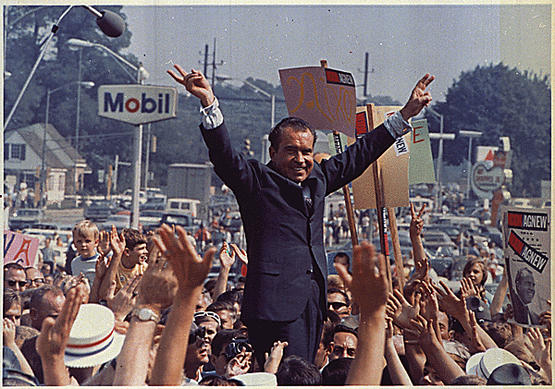

The Republican nominating contest was orderly compared to the Democratic one. Richard M. Nixon swept the Republican primaries and easily won the nomination at the Republican convention against opponents such as Michigan governor George Romney and New York governor Nelson Rockefeller. Nixon ran as the champion of the "silent majority," those who rejected the radicalism and cultural liberalism of the time. He chose the conservative and relatively inexperienced governor of Maryland, Spiro Agnew, as his running mate, partly to appeal to Southern conservatives. A move even more important, as Alabama Governor George Wallace had entered the election as a third-party candidate for the American Independent Party, running on a platform of extreme social conservatism. Wallace railed against “pointy-head intellectuals” and anarchists and for “law and order,” and stood, throughout the campaign, at 20 percent in the polls.

During the general election campaign, Humphrey initially struggled but eventually came back with the help of his running mate Muskie and his pledge, if elected, to stop bombing North Vietnam as “an acceptable risk for peace.” Nixon had a breezy campaign, leading in the polls during most of the general election; so much that he could take the weekend off to rest. A series of televised interviews in October, however, got him into hot water, while Humphrey received McCarthy's support. President Johnson’s announcement that he would suspend air attacks on North Vietnam helped Humphrey close some ground. His last minute surge, however, came too late. On Election Day the popular vote was close: Nixon had 43.4 percent, Humphrey had 42.7 percent, and Wallace won 13.5 percent of the popular vote. But Nixon's Electoral College margin was substantial, 301 to 191 to 46. Despite the closeness of Nixon's victory, it was a resounding mandate against Johnson and the Democratic Party.

Despite heavy campaigning by Vice President Spiro Agnew and Nixon himself during the 1970 midterm elections, the Democrats retained their Senate majority of fifty-four against forty-three for the Republicans, despite losing a net of three seats. The Republicans and the Conservative Party of New York picked up one net seat each, and former Democrat Harry F. Byrd, Jr. was re-elected as an independent. They also increased their majority in the House, picking twelve seats for a balance of 253 against 192 for the Republicans. The increasing fatigue over the ongoing Vietnam War as well as the fallout over the Kent State Massacre are often cited as reason for the Democrats' gains.

Television Coverage

After a stint in Vietnam, Rather resumed his post as White House correspondent in 1966. He played a bigger role in CBS coverage of the 1968 election, covering the two conventions. In Chicago, he was punched in the stomach by security guard as he attempted to question a delegate being escorted out. The scene aired live on TV, prompting Cronkite to exclaim " We have a bunch of thugs here." On election night, Rather was responsible for the Midwest, next to Roger Mudd (South), Mike Wallace (East), and Joe Benti (South). Cronkite anchored the evening, and Eric Severeid offered commentary.

Rather had closely followed the primaries, reporting on them for the CBS Evening News, but also in his radio reports in the series First Line Reports. His brief reports, usually from Washington and less than five minutes long, gave him more freedom in tone and range of topics. From the fall of 1967 on, he speculated on whether Johnson would run or not , introduced listeners to McCarthy after he announced his candidacy, pondered over Kennedy’s decision to run, and analyzed McCarthy's early wins. Rather was on air with Roger Mudd when Johnson announced that he would not seek re-election, a news that took both reporters by surprise and they tried to make sense of it, live on the air.

As candidates made a case for their nomination, one of the major topics to emerge was the issue of televised debate and the “Fairness Doctrine,” which was designed to protect all factions by providing equal airtime on television according to Section 315 of the Communication Act. It became problematic in 1968 when the presumed candidate, Johnson, was also the current president. The Federal Communications Commission tried to distinguish between an appearance as “President of all the people” and his programs as a “candidate.” Network and influential newspapers were pushing for a televised debate before the convention, but the equal time provision led to “migraine” as explained by Variety. As early as May 1968, the network devised a plan presented by CBS News's Franck Stanton to organize political debate with the republican and democratic candidates as well as George Wallace. The plan hinged on congressional approval and the suspension of the equal time provision of the FCC. Networks would otherwise have to give equal time to a number of minor parties, an estimated half-dozen in 1968, as well as the major party candidates.

In May 1968, the Senate commerce committee unanimously approved a resolution to clear the way for televised debates among major presidential candidates, leaving it up to the networks to include or not George Wallace and his American Independent Party. By September, the House commerce committee was scheduled to vote to suspend equal time rule. Although neither Nixon nor Humphrey were originally willing to give Wallace equal billing, the Democratic candidate agreed to a debate, partly as a way to rally Democratic voters. Nixon, who had faired badly against Kennedy in 1960, decided not to participate, something Humphrey used in the campaign.

Building on their successful 1964 and 1966 coverage, networks geared up with an arsenal of computers (RCA SPECTRA 70/45 FOR NBC, IMB System/360s for ABC and CBS). The competition among candidates was as tight one among networks, as the later all hoped to increase sales if declared winners. Among its novelties, CBS used IBM 2250 display units to post results electronically and built a new set, a two-story high circular information center. As predicted, the night was very long, with seventeen hours of continuous coverage, from 6 p.m. to 11 a.m. It was, as Broadcasting put it “the most expensive, extensive and apparently closely watched” election yet, with an estimated 142 million people in the United States. It was found out afterward that the main reason Nixon was not declared the winner several hours earlier was because of an unexpected programming error that forced NES to switch to its backup system.

Just a days after the election, Cronkite sat with the regional correspondents to discuss 'What Happened Last Night."