The Iran-Contra Affair was a clandestine action by the Reagan administration that involved arms sales to the hostile Iran government and the illegal supply of millions of dollars and weapons to the right-wing "Contra" guerrillas in Nicaragua. The Reagan administration repeatedly denied any involvement, raising questions about the use of covert operations, congressional oversight, and even the presidential power to pardon.

Reagan very publicly fought to eradicate communism around the globe, especially in Central America. In 1979, a revolution brought the Sandinistas, a socialist group, to power in Nicaragua. Fearing the spread of similar movements in the region, the Reagan administration decided to back a paramilitary group, the Contras. It was a difficult task as the Democratic congress had passed the Boland Amendment, restricting CIA and Department of Defense operations in Nicaragua specifically after it was found that the Contras were involved in drug trafficking. The amendment was strengthened in 1984, making it impossible to officially support the Contras. In March 1986, President Reagan tried to convince Congress and the American people to spend up to $100 million to help the Contras, but the Contra aid package was defeated. He appealed again to the nation in June of that year.

President Reagan nevertheless ordered its National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane to find a way to help the Contras. The solution was selling weapons to Iran, which in 1985 was at war with its neighbor Iraq, and redirecting the money to the Contras. Although there was an embargo against selling arms to Iran, both McFarlane and Reagan saw this as a way to gain leverage with Iran, in hopes of securing the release of American hostages held in Lebanon by Hezbollah terrorists loyal to the Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran's leader.

In November 1986, the Lebanese newspaper Al-Shiraa broke the story, unveiling the fact that more than 1,500 missiles had been sold to Iran clandestinely. President Reagan went on national television on November 13, 1986, and vehemently denied that his administration had engaged in “arms-for-hostages” operation. An investigation followed, and Attorney General Edwin Meese announced on November 25 that he had discovered a discrepancy of $28 million from the arm sales. President Reagan then commissioned the Tower Commission, whose report published on February 26, 1987, concluded that Reagan's disengagement from the management of his White House had created conditions that made possible the diversion of funds to the Contras. No evidence linking Reagan to the diversion of funds was found, however. After three months of silence, President Reagan expressed regret during a nationally televised address on March 4, 1987, taking full responsibility for the acts committed.

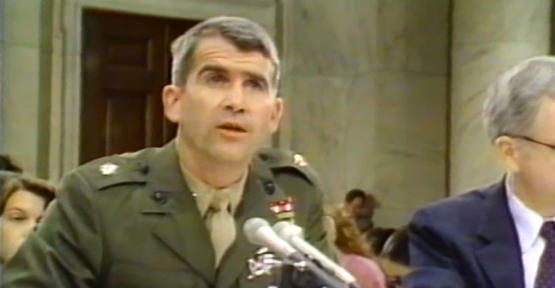

Unsatisfied with the results of the commission, Sen. Daniel Inouye (D-HI), the chair of the Senate Select Committee, called for additional hearings. Joint hearings of House Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transactions with Iran and the Senate Select Committee on Secret Military Assistance to Iran and the Nicaraguan Opposition took place from May 5 to August 6, 1987. In a much-publicized set of testimonies, Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North of the National Security Council explained that he had diverted funds from the arms sales to the Contras, with the full knowledge of National Security Adviser Admiral John Poindexter. He also admitted to destroying or hiding pertinent documents.

The responsibility of then Vice President George H. W. Bush also remained unclear. Bush faced tough questions when he ran for president in 1988 as he kept denying any knowledge and saying he was “out of the loop.” Shortly before leaving office in 1992, President Bush issued six pardons, including one to McFarlane, who had already been convicted, and one to Weinberger before he stood trial. North's conviction had been overturned on a technicality, and President Bush expunged North’s conviction on the grounds that he had acted strictly out of patriotism.

In the last thirty years, numerous documents have surfaced that demonstrate the involvement of President Reagan and Vice President Bush. Through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the National Security Archive obtained, for example, files compiled during Lawrence Walsh's six-year investigation from 1987 to 1993. The documents revealed, among others, that President Ronald Reagan was briefed in advance about every weapons shipment in the Iran arms-for-hostages deals in 1985 and 1986, and Vice President George H. W. Bush chaired a committee that recommended mining of the harbors of Nicaragua in 1983.

Television Coverage

Television news was taken by surprise in November 1986, when Attorney General Edwin Meese announced the findings in his investigation of the National Security Council and its role in the Iran arms sales. They immediately shifted gears and focused on the story. Tom Brokaw talked to Nicaraguan Vice President Sergio Ramirez, and Dan Rather sat with Edwin Meese for a "riveting" interview.

In the following months, all news agencies actively pursued the story, too much for seven in ten Americans, who complained of excessive coverage that was sometimes judged as being politically motivated. According to the Los Angeles Times, most Americans, however, still believed a watchdog press was necessary to keep politicians honest. These results may have been rooted in the president's high approval ratings and the fact that the Iran-Contra affair was very complex. By January 1987 only one-fifth of the respondents of a Gallup Poll said they were following it.

The congressional hearings in the spring and summer of 1987 became a "mega-media event" on their own. As Karen Tumulty reported in the Los Angeles Times, CBS "had built a special glass booth atop a building near the capitol that will make the capitol Dome into a eye catching backdrop for Dan Rather as he anchors the opening of the hearings." Following the opening day, ABC, CBS, and NBC did short broadcasts when important witnesses appeared, such as Major General Richard Secord, or to summarize the main events of the day. Only CNN covered the hearings gavel to gavel. As Broadcasting pointed out, the broadcasting of the hearings by a multitude of networks such as PBS and C-SPAN illustrated the rapidly changing media landscape where satellite technology provided stations flexibility in such special event coverage.

Television news' and the audience's attention was also divided between the hearings and the Gary Hart story, which unfolded and culminated the same week, when the Democratic presidential front-runner withdrew from the running in the wake of revelations about an affair he had had. Later that summer, Oliver North's testimony turned the hearings into a "gripping, first-rate dynamite political theater." The Washington Post described how North acted alternatively "passionate or peevish or whimsical, was righteous or indignant or sardonic, one minute acting the frisky puppy and the next the hounded hangdog." As North became extremely popular, embodying for some a new kind of patriotism, the dynamic in the courtroom changed with members of the committee on the defensive.

As the hearings continued, they turned, in the words of Tom Shales, into a "shower of babble," a "congressional self-caricature of fatuous wind-bagging." Losing between $600,000 and $1 million per day in advertising revenues, ABC, CBS, and NBC reached an agreement where they ceased to cover the hearings from gavel to gavel and instead took turns airing full coverage on alternate days; something they had done in 1974 with the Watergate hearings.

Looking back at the whole scandal in 1990, Scott Armstrong was highly critical of how the press covered the affair. While he praised the early stages of journalistic work, when the pieces of the puzzle were pieced together, he questioned the focus of journalists and pundits alike on the role of the president. They did not follow up on the ramification of the affair, including the role of the Congress and "the use of congressionally appropriated funds to get other countries to do what the U.S. government could not legally do." Similarly, George H. W. Bush's role in the affair was not sufficiently investigated, and Armstrong laid out in detail how the press focused on the confrontation between Dan Rather and George Bush instead of sticking to the substance of the interview and Bush's many factual errors.