The forty-fifth U.S. presidential election took place in 1964. The Democratic candidate, Lyndon B. Johnson, who had become president less than a year earlier following the assassination of his predecessor, John F. Kennedy, won 61.1 percent of the popular vote, the highest win by a candidate since James Monroe’s re-election in 1820. He carried forty-four of the fifty states and won 486 of the 538 electoral votes.

Johnson’s campaign, however, faced numerous challenges, many connected to the landmark Civil Rights Act he had signed in 1964. The segregationist governor of Alabama, George Wallace, ran in a number of northern primaries against Johnson and did surprisingly well in some states, endangering Johnson's position. Despite longstanding animosity between the two men, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy tried to force Johnson to choose him as his running mate. Johnson avoided this by first announcing that none of his cabinet members would be considered for second place on the Democratic ticket and second by scheduling Kennedy’s speech at the convention on the last day, after Senator Hubert Humphrey from Minnesota, a liberal and civil rights activist, had been announced as Johnson’s running mate.

Johnson biggest trouble came during the National Democratic Convention in late August in Atlantic City, New Jersey. After the official Mississippi delegation had been elected by a white primary system, the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) claimed the seats for delegates for Mississippi. A compromise was eventually broken: the MFDP was to take two seats; the regular Mississippi delegation was required to pledge to support the party ticket; and no future Democratic convention would accept a delegation chosen by a discriminatory poll. The compromise angered both sides: white delegates from Mississippi and Alabama refused to sign any pledge and left the convention, and many young civil rights workers were offended by the compromise itself. White southerners began defecting to the Republican Party en masse during the fight over the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and Johnson lost Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina.

On the Republican side, the party was extremely divided between entrenched moderates and conservative insurgents, who were determined to unseat “Wall Street Republicans.” Angry conservatives choose Senator Barry Goldwater from Arizona, who had won key primary victories against Nelson Rockefeller. Despite a last-ditch effort by an anti-Goldwater minority to rally around Governor Scranton, Goldwater was nominated on the first ballot at the Republican convention in July in San Francisco, California. While Johnson’s campaign successfully depicted Goldwater as a dangerous extremist, the latter had a lasting impact on the American political landscape. Goldwater made moral leadership a major theme of his campaign and placed heavy emphasis on lawlessness and crime in big cities; something Nixon would use in 1968. With his refusal to support the Civil Rights Act and his positions on limited government, welfare, and defense, Goldwater marked the beginning of shift to the right. He is credited with building the foundation of the modern conservative movement. In addition, Goldwater approved the televised speech of a film and television star named Ronald Reagan. “A Time of Choosing,” which would catapult Reagan into the national scene and culminate in his election as president in 1980.

The 1966 elections reinstated the Republicans as a large minority in Congress, and social legislation slowed, competing with the Vietnam War for available funds.

Television Coverage

Conventions had been televised since 1952, but 1964 marked a dramatic increase in coverage. In January 1964, CBS announced that it would schedule twenty-one election specials on a broad range of topics, including the candidates, the issues, the possible make-up of Congress, as well as the histories of past campaigns. The first special was an extended report on the New Hampshire primaries. The parties themselves understood the power of television. The Republican National Committee signed Sig Michelson, former CBS News president, as executive program director for the party’s national convention, and Leonard Reinsch, president of Cox Broadcasting, managed the Democratic convention,

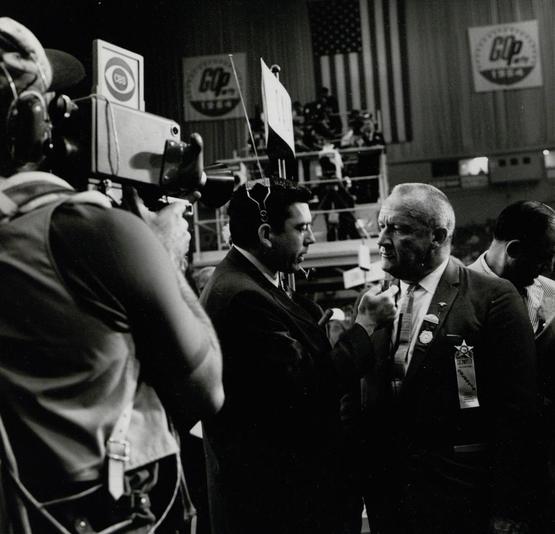

In 1966, Herbert Waltzer wrote a detailed review of television coverage of the 1964 conventions, focusing especially on CBS, in his article “In the Magic Lantern.” CBS started preparing for the 1964 election in November 1962, creating its first permanent Election Unit, which authored the election “notebook” with all vital information about candidates, issues, and locations. The three networks spent between $25 and $30 million in covering the 1964 election, including $15 million for both conventions. CBS more than doubled the number of its staff—600 persons worked at the Republican convention in San Francisco—and doubled the tonnage of equipment. The networks used for the first time new and improved items of equipment, such as wireless and more mobile portable cameras and microphones, and built elaborated news sets in the convention centers. The convention floors were divided into quadrants, each designated to one correspondent with a crew that usually consisted of a cameraman, a soundman, and a producer. The correspondents and their producers were to report “scoops” and “firsts” they had gathered on the floor. This task was somewhat arduous in 1964, when journalists faced angry delegates—a young John Chancellor was even arrested by security at the Republic convention. Dan Rather, who had succeeded George Herman as White House correspondent on February 14, 1964, worked as a floor reporter at both Republican and Democratic conventions in the summer of 1964.

Metzler noted that while television’s goal was to provide a direct link between politician and public, the very presence of television altered the nature of the conventions, from the choice of location (more telegenic) and the procedure (speed up certain procedures to avoid dull moments) to the schedule (major events held during prime time). Films were prepared to show the convention attendees and hopefully the rest of the country through television. Metzler concluded that “television has been blamed for stressing personalities over issues of politics and the telegenic qualities of candidates.”

Walter Cronkite had been the leading man for CBS elections and conventions coverage since 1952. After the network achieved poor ratings during the Republican convention in July 1964, CBS decided to try a two anchors format with Robert Trout and Roger Mudd, in an effort to match the highly successful Chet Huntley–David Brinkley team at NBC, and ABC's experiment with Howard Smith and Edward P. Morgan. On November 3, Cronkite was back, and he anchored election night in November 1964, with Harry Reasoner and Roger Mudd for the presidential race, as well as Bob Trout for Congress and Senate races, Mike Wallace for governor races, and Eric Severeid reporting.

After the conventions, the candidates unleashed a series of televised ads at a a level previously unseen. "Daisy" is considered to have had played a major role in Johnson's victory, and "Confession of a Republican" was 'adapted' during the 2016 campaign. While they attacked each other through televised ads, the two candidates did not, unlike the 1960 election, participate in a nationally televised debate. The main reason being that Johnson was well ahead in the polls and he felt that a debate could not help him much but could certainly hurt him, if he did not do well.

For the first time, election returns were gathered and reported cooperatively by the major media through Network Election Service. The N.E.S. was joint enterprise of the Associated Press, United Press International, and the three television networks. It employed a man or a woman in 130,000 of the nation’s 172,500 voting precincts to speed up the results. Each network, however, developed its own interpretation team in a battle of computers, pollsters, and election interpreters. CBS created a new unit called V.P.A .or Voting Profile Analysis, in collaboration with International Business Machines computers (IBM) and Louis Harris, a political pollster. On November 4, CBS was declared the clear winner of election night coverage. Using the V.P.A. system, CBS was able to be the first declare the president around 9:04 p.m. on the basis of electoral vote projection and the use of analytical research. As laid out by the Los Angeles Times, NBC won in the ratings but CBS was considered the superior broadcast, because of the greater visual appeal and the clever use of its election boards and Louis Harris’s predictions.