In his twenty-four-year tenure as the anchor and managing editor of the CBS Evening News, Dan Rather witnessed, and was part of, numerous transitions and transformations of CBS News and television broadcasting as a whole.

The most drastic change was the plummeting of the percentage of U.S. households watching the Big Three networks (ABC, CBS, NBC) during prime time: from 43 percent to 19 percent between 1980 and 2005. The news divisions faced heightened competition with each other, and new satellite technologies gave more power to local stations that then directly competed with the networks. The advent of cable news channels from CNN and Fox News to MSNBC altered the mission and the format of traditional evening news and, more recently, the internet radically changed the makeup of the American media landscape.

A parallel trend was the widespread deregulation that started in the 1980s and enabled the eradication of public-service requirements as well as the increased corporatization of the media and its consolidation in a handful of owners. In 1983, fifty corporations controlled most of the American media, including magazines, books, music, news feeds, newspapers, movies, radio, and television. By 1992 that number had dropped by half and by 2000, only six corporations had ownership of most media. In 2017, five dominate the industry: Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, and Viacom CBS corporation. This development is highly problematic as it first limits the spectrum of viewpoints that have access to mass media. Secondly, independent journalism is compromised because U.S. media outlets are overwhelmingly owned by for-profit conglomerates and supported by corporate advertisers, potentially restricting the types of investigations being done.

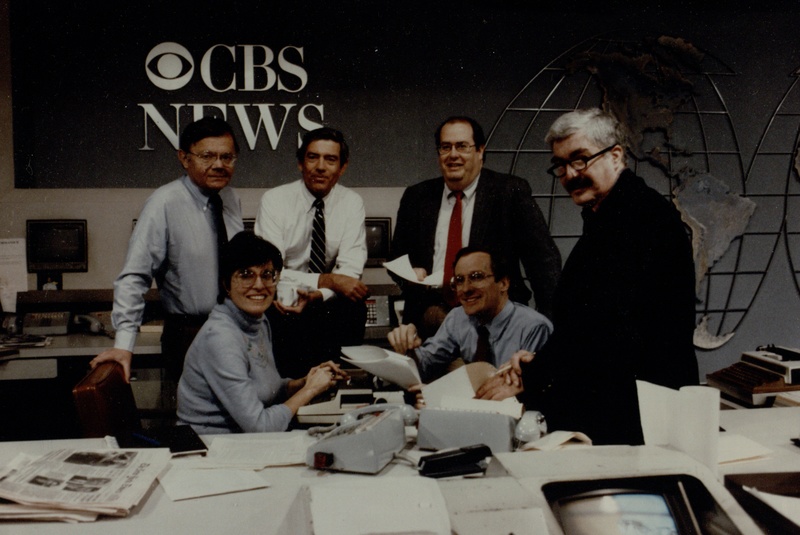

Transitions at CBS News

CBS itself, and especially the news department, went through tumultuous years in the 1980s as the corporate culture took precedence over journalistic responsibility.

As entertainment programs' costs rose and their returns diminished, news programs were increasingly seen as “the network television’s hottest commodity.” There was a mounting pressure to do well in the ratings as a way of ensuring more advertisement incomes. This was a sharp departure from the practices and philosophy of the CBS News division, once America’s number-one news network. Starting with Edward R. Murrow, who covered live the conflicts in Europe during World War II on the radio, the CBS news division established the standards for fairness and accuracy in reporting that other networks embraced.

In the early 1980s, CBS News faced falling ratings and heightened competition by ABC and NBC. Other problems included a $120 million libel suit filed by General Westmoreland and the much-criticized hiring of former beauty queen Phyllis George as co-anchor of the CBS Morning News. In December 1981, the network appointed Van Gordon Sauter to succeed Bill Leonard as president of CBS News. To help the struggling Evening News, Sauter replaced Cronkite's longtime producer Sandy Socolow with Howard Stringer, who tailored the Evening News to fit Dan Rather’s style, built a new set, and employed different camera angles. Snappy graphics and visual techniques were introduced to move away from the “headline service” type of evening news, but Sauter also facilitated the return of commentator Bill Moyers and approved longer features on the Evening News. He instituted an almost daily postmortem on the broadcast, analyzing and grading each segment—something producers like Lane Venardos found helpful.

While these changes appeared to stem the ratings slippage, many were concerned that CBS News would loose its focus on pure news with the use, for example, of more flashy graphics in pursuit of ratings. Especially problematic for many was Sauter’s “theory and practice of moments,” described by Esquire as “a portrait of an emotional reality, an emblem, a visual reflection of a feeling.” Their defenders argued that the moments made the Evening News more accessible and relevant for millions of viewers, who could now see how Washington decisions affected their lives. For their critics on the other hand, they were a “syrupy travesty of the perceived reality,” turning CBS News into a network version of local television, in what the Columbia Journalism Review called the “sauterizing of news.” By the end of 1982, however, CBS Evening News was back in first place in the ratings.

“The emphasis on ratings and profits is widely perceived as the single greatest threat to the quality of network news."

—The Los Angeles Times, December 12, 1986

These early changes in the direction of the news division were precipitated in the mid 1980s by two hostile takeover bids. The first one was the result of an alliance between the conservative group Fairness in Media and Sen. Jesse Helms (R., N.C.) who pledged to combat what he perceived as the “liberal bias” of CBS News. They encouraged conservatives to buy CBS stocks, and Helms boasted that he would become “Dan Rather’s boss.” Meanwhile, Ted Turner launched his own bid for control of CBS. In order to resist these take-over attempts, CBS bought back 21 percent of its stock, increasing its indebtedness to a rousing $1 billion. To offset these expenses, the network ordered several waves of staff cuts across its divisions, including a 125 people or 10 percent cut in news staff in September 1985 and another 90 people in June 1986.

So dire was the situation that a group of CBS journalists, including 60 Minutes producer Don Hewitt, offered to buy the network. Many blamed inefficient corporate decisions, especially from Chairman and Chief Executive Office Thomas Wyman’s leadership, but Wyman was under intense corporate pressure to increase stock prices and profits. CBS eventually invited Laurence A. Tisch, the chairman of Loews Corp, thought to be a “whitesquire” whose business experience would save the network. Tisch quietly expanded his share of the company from 5 percent to 25 percent and wrestled control of the company from chairman Wyman, who soon after left CBS, as did Van Gordon Sauter.

Like his competitors, Capital Cities Communications, Inc, which merged with ABC, and General Electric after its merger with NBC, Tisch led CBS purely as a business, whose main goal was to make money. While television networks had always been privately owned, the news division was “largely insulated from the struggles of the marketplace." It was considered the prestige unit, one that was not expected to make profits. The success of 60 Minutes, which in 1986 had an annual profit of about $60 million, changed that. News programs were now expected to make money.

A new wave of cuts was seen as necessary, but it became clear that Tisch was not only cutting the fat but also cutting the muscle of CBS News, eliminating foreign bureaus, for example. The Writers Guilds of America went on strike as a protest, and Rather, who showed his support by marching with the picket line, wrote with Richard Cohen a New York Times op-ed piece titled, “From Murrow to Mediocrity,” in which he denounced the recent cuts. The Los Angeles Times bemoaned the “demise of modern news broadcasts” with less documentaries, less hard-edged commentaries. The arrival of satellite technology, which made possible instantaneous transmission from around the globe, produced “rush-to-judgment mentality that often leaves little time for real reporting or reflection and, inevitably, results in rampant superficiality.” By the end of 1986, CBS was, according to the New York Times, “In Search of Itself.”

Between 1988 and 1990, no less than three books were published analyzing the struggles between public versus shareholder responsibility and they bemoaned, among others, the “sell-out of CBS News.” These included Peter McCabe, Bad News at Black Rock: The Sell-Out of CBS News, 1987; Peter Boyer, Who Killed CBS?: The Undoing of America's Number One News Network, 1988; and Ken Auletta, Three Blind Mice: How the TV Networks Lost their Way, published in 1990.

The financial and corporate upheavals directly impacted CBS News, which fell in the ratings behind ABC News. The news division went through successive waves of reorganization, including four presidents (Van Gordon Sauter, Howard Stringer, David Burke, and Eric Ober) and a number of executive producers, from David Bucksbaum and Lane Venardos to Tom Bettag, who was replaced by Erik Sorenson in the spring of 1992. As the CBS Evening News lingered in third place in the Nielsen ratings, the network experimented unsuccessfully with co-anchor Connie Chung. Andrew Heyward became executive producer of the CBS Evening News in 1994 and was later replaced by Jeff Fager in 1996.

Meanwhile, in November 1995, Westinghouse Electric Corporation acquired CBS for $5.4 billion. With the purchase of the television syndication company King World Production and the radio stations owner Infinity Broadcasting Corporation, CBS became a broadcasting giant. Each move was accompanied by cuts. How problematic the entanglement of corporate and news divisions was became apparent when 60 Minutes delayed the airing of a piece on the Brown & Williamson Tobacco Company because CBS layers feared a lawsuit as Tisch was in the final stages of selling CBS to Westinghouse. The New York Times described in 1997 how "corporate pressure is on to pump up the network stars, pep up the scenery and, pardon the expression, dumb down the content." In 2000, CBS was bought by Viacom, which then became the second-largest entertainment company in the world. To facilitate operation, Viacom split the company into two entities, CBS Corporation and Viacom, both owned by National Amusements, the Sumner Redstone-owned company.