Held on November 2, 1976, the forty-eighth United States presidential election saw the victory of Democrat Jimmy Carter over Republican President Gerald R. Ford, who had succeeded Richard Nixon after the latter resigned in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal.

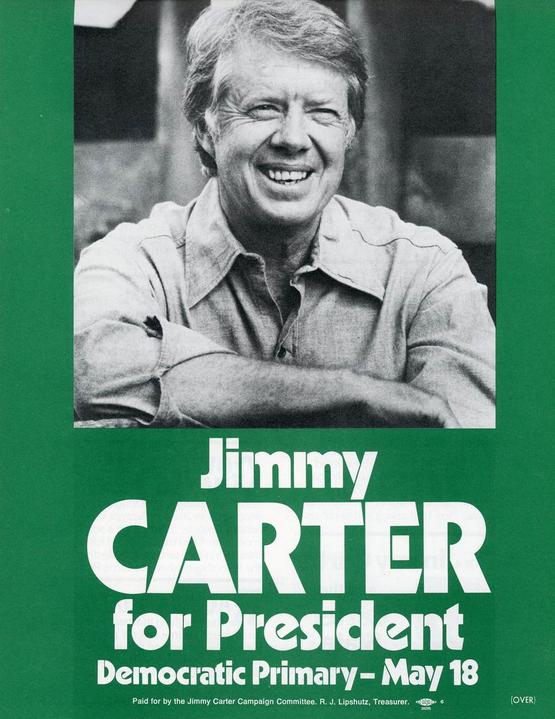

Seventeen Democrats competed in the primaries, but it would be Jimmy Carter, a single-term Georgia governor, who got the nomination. Carter carefully prepared his campaign since 1972 before he announced his candidacy in December 1974. Although he was unknown, had no apparent political base, no organization, no standing in the polls, and little to no money for his campaign, Carter played on his background as a naval officer, a peanut farmer, an agribusinessman, and a late-blooming state politician. As a Georgian and a “New Southerner,” Carter could appeal to both white and African Americans. This was a decisive advantage over competitors as it had become clear in the recent elections that a Democrat could only win the presidency with the support of the “Old South.” If Carter could overcome Northerners’ fear about his fundamentalist, born-again Christian, Southern Baptist faith, he had a slim chance. In addition, in an era marked by cynicism and anger toward Washington and politics, his campaign on issues of “love” and “trust” resonated with many.

It was a long shot until the nomination. Following the advice of his campaign manager Hamilton Jordan to contest the nomination everywhere possible, Carter entered thirty presidential primaries in 1976. It was a way to get much needed exposure as a relative unknown, and he hoped that the new Democratic Party’s rules would give him a proportionate share of delegates even in states where he did not finish first. The plan worked, and by June 8, the final day of the primaries, his nomination was a foregone conclusion. His choice of Senator Walter Mondale and his moderate-to-liberal platform sealed the deal. The keynote address at the Democratic National Convention was delivered by Barbara Jordan, a black woman. Her opening words reflected the historic nature of this fact: "It was one hundred and forty-four years ago that members of the Democratic Party first met in convention to select a presidential candidate. Since that time, Democrats have continued to convene once every four years and draft a party platform and nominate a presidential candidate. And our meeting this week is a continuation of that tradition. But there is something different about tonight. There is something special about tonight. What is different? What is special? I, Barbara Jordan, am a keynote speaker."

Things were more complicated for Gerald Ford, the ‘accidental president.” Ford won in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Florida but his conservative challenger, former California governor Ronald Reagan, won his own share of states, including Texas and California. Reagan challenged Ford in all of the primaries. Ford and Reagan arrived at the convention with nearly the same number of delegates. Ford was nevertheless nominated on the first ballot. He chose Senator Bob Dole of Kansas to strengthen his base in the Midwest, and because Dole was was favored by the conservative wing of the party. In his acceptance speech, Ford challenged Carter to a series of debates in what is often considered the best speech of his career. Ronald Reagan, however, demonstrated that he was the Republican Party's most eloquent speaker when his speech at the close of the convention outshone Ford's speech accepting the nomination.

With the worst recession since the Great Depression and the worst inflation in U.S. history, the economy was a major campaign issue, as was abortion after the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade ruling, and the character of the candidates. Carter was lambasted for changing positions and for his Playboy interview, while Ford had his own struggles, from his hasty pardon of Nixon to his struggles in tackling economic problems. The two men debated three times, and a fourth debate featured the vice presidential nominees. While he performed well in the first debate, Ford’s blunders in the second debate, including his famous statement “there is no Soviet domination of eastern Europe, and there never will be under a Ford administration” damaged his campaign.

Although Carter’s lead in the polls dwindled from thirty to tenpoints, his “Southern Strategy” paid off. The South, which had increasingly gone Republican since 1960, voted Democrat. Carter won 50 percent of the popular vote and 297 of the electoral vote, against 240 for Ford (one elector voted for Reagan).

As the country was suffering from the impact of the energy crisis and faced rapid inflation, the Democrats lost seats to the Republicans in the 1978 House of Representatives elections. While they lost their two-thirds majority, they still retained a rather large majority of 277 seats against 158 for the Republicans. Thirteen seats changed hands in the Senate race, and the balance was 58–41 in favor of the Democrats. The newly elected Republican congressmen were more conservative than their predecessors, setting the stage for what is commonly known as the "Reagan Revolution." One of the most important initial impacts of the new makeup pf congress was ending the possibility of a ratification of the SALT II treaty with the Soviet Union.

Television Coverage

CBS once again filed a petition to loosen the regulations that restricted broadcasters in political matters, especially the equal time provision of Section 315 of the Communication Act. According to the section, broadcasters that aired the press conference of a president who was a candidate for election were subject to demands for equal time from his opponents. Representative Shirley Chisholm and the National Organization for Women, as well as the Democratic National Committee, were against the CBS proposal. In September 1975, the FCC ruled that candidates’ news conferences and political debates would no longer trigger equal-time access for all their opponents. Under the “fairness doctrine,” however, networks were still required to report conflicting views on public issues. This led to some initial confusion, with networks turning down the president’s request to address the nation out of concern about equal-time obligations, but the ruling altogether facilitated the work of the networks and opened up the way for the first presidential debates since 1960. also had a direct impact on the campaign. President Ford, who had been mostly off-camera since the beginning of his campaign so that his opponents would not get equal time, gave more news conferences, and was altogether more publicly present. As the New York Times put it in October 1975, “access to television will be one of the disturbing issues surrounding the 1976 national election campaigns.”

After Nixon resigned, Dan Rather moved from White House correspondent to CBS Reports and later 60 Minutes correspondent. He continued, however, to closely follow U.S. politics and report on it in his radio column, "First Line Reports." As early as September 1975, Rather noted that Ford, not the best orator, multiplied public speeches across, in an attempt to “drive down the chances of Reagan mounting a major threat for the nomination,” and to “shop around for a vice president." Rather examined the crowded Democratic field, with no clear contender in the fall of 1975. Both parties focused on the economy, which showed signs of recovery in early 1976, and for the Democrats, unpopular busing. As the fight between Ford and Reagan intensified in the spring of 1976, Carter emerged as the leading candidate.

After the first act of the primaries, audience and networks got ready for the second act, the conventions, with an estimated combined cost of $30 million. As in the past, CBS and NBC planned gavel-to-gavel coverage, preempting regular programs, and ABC once again offered selective coverage. For the first time, electronic cameras (with tapes) were widely used, replacing film cameras that required chemical processing before the film could be viewed and edited, with the risk of the film breaking during editing. The Democrats chose Madison Square Garden in New York City for their convention, set to take place from July 12 to July 15, sandwiched between the extravagant Bicentennial celebrations and the Summer Olympics. Despite physical limitations, traffic, and tall buildings, preparations went without major logistical problems. Learning from the painful 1972 lesson, where the nomination of Senator George McGovern was not announced until 2 in the morning, when no one was watching, the Democrats set up a carefully planed convention, well aware that “an American political convention cannot succeed unless it succeeds as a television event.” With its infighting between Reagan and Ford supporters and suspense around Ford's vice presidential choice, the Republican convention in Kansas City in August attracted more viewers who did not appear to be bothered by the noisy twenty-five-minute demonstration on behalf of Governor Reagan. Walter Cronkite anchored both conventions with Dan Rather, Roger Mudd, Mike Wallace, and Bruce Morton, was well as Morton Dean and Bob Schieffer. Russ Bensley was once again the producer in charge of convention coverage.

In his acceptance speech, Ford had challenged Carter to a debate, and the lifting of the equal time provision of Section 315 opened the way for a series of three debates between the candidates as well as one between the vice presidential candidates, all of which were sponsored by the League of Women Voters Education Fund (LWVEF), which escaped the requirements of section 315. Negotiations between the league and the networks grew tense, over issues such as permission to take shots of the audience during the debates, the choice of the panel members who asked the questions, and various other rules. Eventually, ABC, CBS, NBC, and PBS broadcasted the debates.

On September 23, 1976, the first debate on domestic policy was moderated by NBC's Edwin Newman. New Yorker magazine's Elizabeth Drew, Wall Street Journal's James Gannon and ABC's Frank Reynolds were the panelists, and the topic was domestic affairs. A short circuit in a tiny electronic capacitor knocked out the only amplifier, silencing the candidates for twenty-seven minutes. Ford went on the attack right away and was declared a winner in surveys. The second debate took place on October 6, 1976, in San Francisco and was moderated by Pauline Frederick from NPR. Max Frankel of the New York Times, Henry L. Trewitt of the Baltimore Sun, and Richard Valeriani from NBC News were the panelists. The format was slightly altered for the second debate: follow-up questions by panelists were discouraged as a way to create more of an exchange (and a sense of conflict) between the candidates. Answers would be limited to three minutes, with a two-minute rebuttal by the opponent The second debate focused on foreign policy, an area Ford was supposed to be an expert in. The sitting president, however, committed his biggest blunder, declaring that there was no Soviet domination in Eastern Europe. In addition, Carter looked more relaxed and confident. The final debate on October 22, 1976, was moderated by Barbara Walters of ABC News, with syndicated columnist Joseph Kraft, Robert Maynard of the Washington Post, and Jack Nelson of the Los Angeles Times, as panelists.

The presidential race was extremely tight. On the eve of the election, networks were bracing themselves for a long night, hoping that the millions of dollars they had spent would help them to be the first to project the winners of ninety-three races—the presidential election in all states and forty-seven contests for the Senate and governorships. CBS used "stratified ratio estimation," a method deemed more "scientific" and statistically sophisticated. 3,600 precincts were randomly chosen, and statistics on their past voting behavior were entered in a computer and the sample estimated was corrected by the precincts' known past votes by Warren J. Mitofsky, CBS chief sample statistician. The result was a 99 percent accuracy in the 269 projections.

Networks were cautious about calling the presidential results, and CBS did not project Carter's win until 3:46 a.m. It was "one of the biggest election cliffhangers in recent memory." Walter Cronkite anchored the ten-hour live event with Dan Rather (Midwest regional correspondent); Lesley Stahl (West); Bill Moyers and Eric Severeid (analysis desk); Roger Mudd (South); Mike Wallace (East); and Bruce Morton, trend desk correspondent. The Washington Post commented on the next day that "the best part of CBS was Rather's enthusiasm. He had the most closely contested part of the country to report—the Midwest—and he communicated both solid information and excitement."