In the United States presidential election of 2000, Republican George W. Bush narrowly lost the popular vote to Democrat Al Gore but defeated Gore in the electoral college.

Bill Clinton's vice president for eight years, Al Gore announced his candidacy in June 1999. He easily fought off a challenge from the former U.S. senator from New Jersey, Bill Bradley, and won the nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles. He nominated Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman as his running mate. The race was much closer on the Republican side, where Texas Governor George W. Bush, son of President George H. W. Bush, struggled against Arizona Senator John McCain, businessman Steve Forbes, diplomat and conservative commentator Alan Keyes, Utah Senator Orrin Hatch, and conservative activist Gary Bauer. Bush won the nomination and chose former Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney as his running mate.

Gore initially led in the polls as he could boast of the strong and growing economy. With his long record of public service—he had served in Vietnam, and had been a newsman, a U.S. Congressman, a U.S Senator, and a two-term vice president of the United States—it looked like he would easily defeat Bush, who was in his second term as the governor of Texas. Although Clinton was still popular, Gore sought to distance himself from the Monica Lewinsky scandal and Clinton’s impeachment trial. During the campaign, both candidates focused primarily on domestic issues, such as economic growth, the federal budget surplus, health care, tax relief, and reform of social insurance and welfare programs, particularly Social Security and Medicare. Gore’s wooden appearance paled against Bush, the folksy Texas rogue, whose campaign strategy team of Karl Rove, Karen Hughes, and Joe Allbaugh, helped with his “compassionate conservatism” slogan and a promise to restore honor and integrity to the White House. Gore’s campaign, on the other hand, had a hard time zeroing in on a message and stood incredulous as news outlets went after the candidate with misquotes, distortions, and strangely off-the-mark needling. By the end of October, Bush had closed the gap in the polls.

On election night no clear winner emerged. Gore garnered 255 electoral votes to Bush’s 246, but neither candidate won the 270 electoral votes necessary for victory. Elections in New Mexico and Oregon were to close to call, and the race ultimately focused on Florida and its twenty-five electoral votes. Networks first projected Gore as the winner, but later retracted the news and announced it was Bush. Gore called Bush to concede the election, but, as it became clear that the margin of votes in Florida was extremely small (fewer than six hundred votes), Gore retracted his concession around 3:00 a.m.

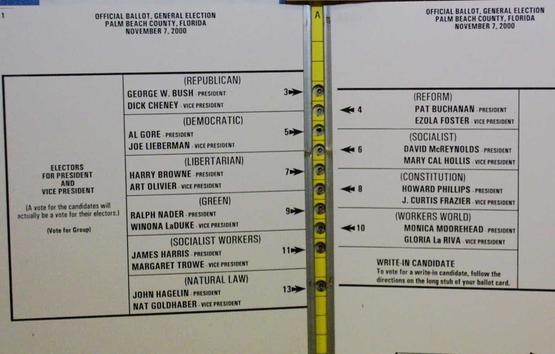

The result in Florida was so close as to trigger a statewide mandatory machine recount according to the Florida Election Code. Completed on November 10, the recount showed that Bush’s lead stood at 327 votes out of 6 million votes. The Gore campaign then requested that the disputed ballots in four counties be recounted by hand. The Florida Supreme Court extended the deadline for the recount and ordered a manual recount. The following weeks were filled with images of county officials trying to discern voter intent through a cloud of “hanging chads” (incompletely punched paper ballots) and “pregnant chads” (paper ballots that were dimpled, but not pierced, during the voting process), as well as “overvotes” (ballots that recorded multiple votes for the same office) and “undervotes” (ballots that recorded no vote for a given office). In addition, the so-called butterfly ballot design used in Palm Beach County was called into question. It was very confusing and led some Gore voters to inadvertently cast their votes for third-party candidate Pat Buchanan, who received some 3,400 votes (approximately 20 percent of his total votes statewide).

By late November the Florida state canvassing board certified Bush the winner by 537 votes, but the election still was unresolved, as legal battles remained. Eventually, the Florida Supreme Court decided (4–3) to order a statewide manual recount of the approximately 45,000 undervotes—ballots that machines recorded as not clearly expressing a presidential vote—and accepted some previously uncertified results in both Miami-Dade and Palm Beach counties, reducing Bush’s lead to a mere 154 votes. The Bush campaign quickly filed an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court, asking it to delay the recounts until it could hear the case; a stay was issued by the court on December 9. Three days later, concluding that a fair statewide recount could not be performed in time to meet the December 18 deadline for certifying the state’s electors, the court issued a controversial 5–4 decision to reverse the Florida Supreme Court’s recount order in the now famous Bush v. Gore case, effectively awarding the presidency to Bush.

With Florida in his column, Bush narrowly won the electoral vote over Gore by 271 to 266—only one more than the required 270 (one Gore elector abstained). Gore, however, won the popular vote over Bush by some 500,000 votes—the first inversion of the electoral and popular vote since 1888. Ralph Nader and the Green Party won 2.7 percent of the popular vote and were vilified by some Democrats, who accused them of spoiling the election for Gore. The true impact of the Green Party in the 2000 election remains controversial.

Television Coverage

2000 marked a stark departure in the way television covered the election. The three big networks, ABC, CBS, and NBC, drastically reduced their coverage, leaving instead their cable competitors, CNN, C-SPAN, MSNBC, and Fox News as the dominant source of political news. All but two of the primary debates were broadcast on network television, and CBS News, “whose election coverage was once considered the most thorough and informed on television,” only aired one. Dan Rather, who did not moderate any of the debates, regretted the shift away from political coverage, calling it part of the networks' public responsibility and that “we have abrogated that civic trust.”

In the primaries, the networks sent fewer reporters to follow the candidates and moved their in-depth reporting to their websites. CNN was highly involved in the campaign, however, producing 144 programs on politics during the Iowa and New Hampshire primaries. CNN dramatically increased its coverage of the conventions in Los Angeles and Philadelphia, asking for not one but four skybooths in each convention hall, while the networks reduced their presence. CBS only had two floor correspondents, Ed Bradley and Bob Schieffer, and slipped convention reports into its standard newsmagazines 48 Hours and 60 Minutes II. They only provided live coverage from 9 or 10 until 11 p.m. Eastern time, or later when President Clinton gave his speech. Jim Lehrer on the other hand, anchored PBS's coverage of the conventions from 8 to 11 p.m. At the Republican convention in Philadelphia from July 31 to August 3, Bush emphasized the image of a more sensitive and moderate Republican Party, a message at odds with the party’s conservatism. He gained a lot of ground by capitalizing on the party’s traditional strengths, moral values, especially in the aftermath of the Clinton scandals. In addition to Dick Cheney and Colin Powell, John McCain, Norman Schwarzkopf, and Condoleezza Rice spoke at the convention. The Los Angeles Times called George W. Bush's delivery “undistinguished. It was uneven, at once conversational and mechanical.” Held in Los Angeles from August 14 to 17, 2000, the Democratic convention featured speeches by Caroline Kennedy and Senator Ted Kennedy, both judged quite dull by the Washington Post, and an insightful speech by Jesse Jackson. Because of delays, the speech of First Lady Hillary Clinton as well as President Clinton’s speech were broadcast in full, prompting Republicans to cry foul. Al Gore’s speech was described as being populist, focusing on the defense of working families and issues like tax cuts and health care. The Democratic nominee tried to appeal to, or not turn away, swing voters. Numerous protests took place outside of the convention center as well as throughout downtown Los Angeles. They turned violent on the first night of the convention and many people were arrested.

Three presidential debates were organized by the non-profit Commission on Presidential Debates on October 3, 11, and 17, while the vice presidential debate took place on October 5. The commission set up a requirement that only candidates who received support from 15 percent of voters surveyed by five national polling organizations could participate in the debates, and only George W. Bush and Al Gore qualified. The commission then barred third-party candidates Ralph Nader of the Green Party and Patrick J. Buchanan of the Reform Party from the debate audiencse, for fear they would be a disruptive presence. According to the Los Angeles Times, Bush came out of the first debate as a winner by virtue of not making a fool of himself while Gore “won” in terms of points made and by looking more poised and presidential. Gore, however, came across at time as condescending, something the show Saturday Night Live parodied extensively; a parody that was in turn used by the Gore team for preparation for the second debate. Dan Rather was “the bluntest” in his assessment of the first debate, calling it a “joint appearance,” that was inducement to “narcoplepsy” with long, dull and tiring stretches. The Los Angeles Times thought that “CBS did the best post-debate show of any of the networks,” and in their un-scientific poll 34 percent saw Bush as the winner, and 49 percent voted for Gore. The press agreed that the first debate, "devoid of memorable moments or crippling mistakes," did not change much. The second debate was a roundtable discussion and the third a town hall meeting where the candidates answered questions from an audience.

As the networks readied for election night, they braced themselves for a long night as the two candidates were neck-in-neck in the polls. While they had had close to 100 percent accuracy calling elections in the previous decades, television news outlets from ABC to CNN first called Florida for Gore around 8 p.m. and later retracted the announcement around 10 p.m. Just after 2 a.m, they then called the presidency for Bush, and at 2:30 a.m., Gore telephoned Bush and offered his congratulations, conceding the election. When the networks reversed their call as Bush's lead in Florida shrunk to 1,655 votes, Gore telephoned Bush once more and this time "un-conceded."

The outlets admitted their errors the next day and started reexamining how they projected winners. The various networks used their own exit polling and coordinated the surveying through the Voter News Service, which collects data at polls across the country and feeds it to news outlets. Networks in turn perform their own analysis. While it appeared that some of the data provided by the VNS was faulty, the networks also called Florida before the polls closed in the Western Panhandle region of the state, which is in a different time zone, as hundreds of thousands of votes were still unaccounted. Needless to say, competition and the need to be the first to call the election pressured journalists to make quick judgments. News division executives were called months later before a congressional committee to explain themselves. CBS ordered an internal investigation and made an extensive report public in January 2001. In early 2003, the Voter News Service was disbanded by the six news organizations that had created it in 1988. Instead, ABC, CBS, NBC, CNN, Fox News, and the Associated Press reached an accord with Warren Mitofsky of Mitofsky International and Joseph Lenski of Edison Media Research to form the National Election Pool.

In the following thirty-six days, the networks covered the ensuing political and legal turmoil, attempting to translate, often live, the arcane and legal jargon used in the process.