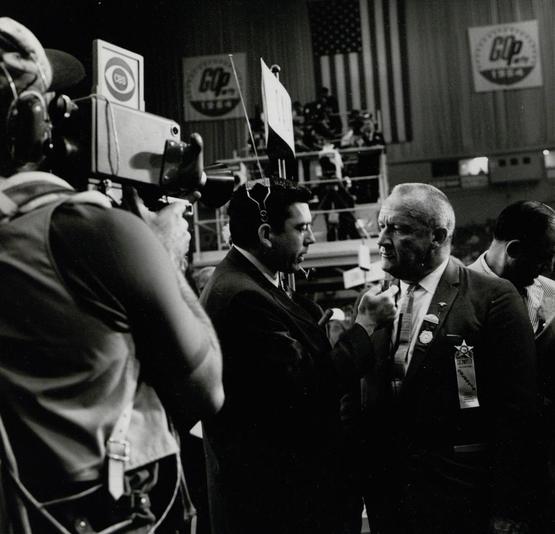

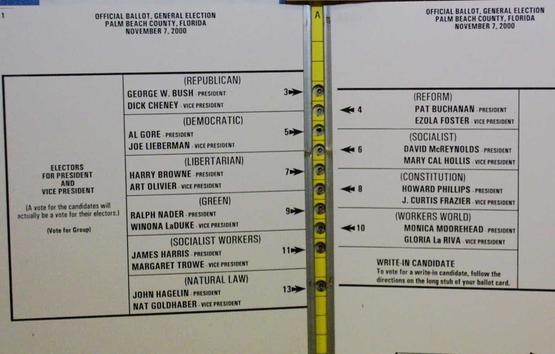

Dan Rather interviews a delegate during the 1964 Republican Convention. Rather (Dan) Papers, Box 79_0005, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, Boston University.

The forty-fifth U.S. presidential election took place in 1964. The Democratic candidate, Lyndon B. Johnson, who had become president less than a year earlier following the assassination of his predecessor, John F. Kennedy, won 61.1 percent of the popular vote, the highest win by a candidate since James Monroe’s re-election in 1820. He carried forty-four of the fifty states and won 486 of the 538 electoral votes.

Johnson’s campaign, however, faced numerous challenges, many connected to the landmark Civil Rights Act he had signed in 1964. The segregationist governor of Alabama, George Wallace, ran in a number of northern primaries against Johnson and did surprisingly well in some states, endangering Johnson's position. Despite longstanding animosity between the two men, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy tried to force Johnson to choose him as his running mate. Johnson avoided this by first announcing that none of his cabinet members would be considered for second place on the Democratic ticket and second by scheduling Kennedy’s speech at the convention on the last day, after Senator Hubert Humphrey from Minnesota, a liberal and civil rights activist, had been announced as Johnson’s running mate.

Johnson biggest trouble came during the National Democratic Convention in late August in Atlantic City, New Jersey. After the official Mississippi delegation had been elected by a white primary system, the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) claimed the seats for delegates for Mississippi. A compromise was eventually broken: the MFDP was to take two seats; the regular Mississippi delegation was required to pledge to support the party ticket; and no future Democratic convention would accept a delegation chosen by a discriminatory poll. The compromise angered both sides: white delegates from Mississippi and Alabama refused to sign any pledge and left the convention, and many young civil rights workers were offended by the compromise itself. White southerners began defecting to the Republican Party en masse during the fight over the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and Johnson lost Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina.

On the Republican side, the party was extremely divided between entrenched moderates and conservative insurgents, who were determined to unseat “Wall Street Republicans.” Angry conservatives choose Senator Barry Goldwater from Arizona, who had won key primary victories against Nelson Rockefeller. Despite a last-ditch effort by an anti-Goldwater minority to rally around Governor Scranton, Goldwater was nominated on the first ballot at the Republican convention in July in San Francisco, California. While Johnson’s campaign successfully depicted Goldwater as a dangerous extremist, the latter had a lasting impact on the American political landscape. Goldwater made moral leadership a major theme of his campaign and placed heavy emphasis on lawlessness and crime in big cities; something Nixon would use in 1968. With his refusal to support the Civil Rights Act and his positions on limited government, welfare, and defense, Goldwater marked the beginning of shift to the right. He is credited with building the foundation of the modern conservative movement. In addition, Goldwater approved the televised speech of a film and television star named Ronald Reagan. “A Time of Choosing,” which would catapult Reagan into the national scene and culminate in his election as president in 1980.

The 1966 elections reinstated the Republicans as a large minority in Congress, and social legislation slowed, competing with the Vietnam War for available funds.

Television Coverage

Conventions had been televised since 1952, but 1964 marked a dramatic increase in coverage. In January 1964, CBS announced that it would schedule twenty-one election specials on a broad range of topics, including the candidates, the issues, the possible make-up of Congress, as well as the histories of past campaigns. The first special was an extended report on the New Hampshire primaries. The parties themselves understood the power of television. The Republican National Committee signed Sig Michelson, former CBS News president, as executive program director for the party’s national convention, and Leonard Reinsch, president of Cox Broadcasting, managed the Democratic convention,

In 1966, Herbert Waltzer wrote a detailed review of television coverage of the 1964 conventions, focusing especially on CBS, in his article “In the Magic Lantern.” CBS started preparing for the 1964 election in November 1962, creating its first permanent Election Unit, which authored the election “notebook” with all vital information about candidates, issues, and locations. The three networks spent between $25 and $30 million in covering the 1964 election, including $15 million for both conventions. CBS more than doubled the number of its staff—600 persons worked at the Republican convention in San Francisco—and doubled the tonnage of equipment. The networks used for the first time new and improved items of equipment, such as wireless and more mobile portable cameras and microphones, and built elaborated news sets in the convention centers. The convention floors were divided into quadrants, each designated to one correspondent with a crew that usually consisted of a cameraman, a soundman, and a producer. The correspondents and their producers were to report “scoops” and “firsts” they had gathered on the floor. This task was somewhat arduous in 1964, when journalists faced angry delegates—a young John Chancellor was even arrested by security at the Republic convention. Dan Rather, who had succeeded George Herman as White House correspondent on February 14, 1964, worked as a floor reporter at both Republican and Democratic conventions in the summer of 1964.

Metzler noted that while television’s goal was to provide a direct link between politician and public, the very presence of television altered the nature of the conventions, from the choice of location (more telegenic) and the procedure (speed up certain procedures to avoid dull moments) to the schedule (major events held during prime time). Films were prepared to show the convention attendees and hopefully the rest of the country through television. Metzler concluded that “television has been blamed for stressing personalities over issues of politics and the telegenic qualities of candidates.”

Walter Cronkite had been the leading man for CBS elections and conventions coverage since 1952. After the network achieved poor ratings during the Republican convention in July 1964, CBS decided to try a two anchors format with Robert Trout and Roger Mudd, in an effort to match the highly successful Chet Huntley–David Brinkley team at NBC, and ABC's experiment with Howard Smith and Edward P. Morgan. On November 3, Cronkite was back, and he anchored election night in November 1964, with Harry Reasoner and Roger Mudd for the presidential race, as well as Bob Trout for Congress and Senate races, Mike Wallace for governor races, and Eric Severeid reporting.

After the conventions, the candidates unleashed a series of televised ads at a a level previously unseen. "Daisy" is considered to have had played a major role in Johnson's victory, and "Confession of a Republican" was 'adapted' during the 2016 campaign. While they attacked each other through televised ads, the two candidates did not, unlike the 1960 election, participate in a nationally televised debate. The main reason being that Johnson was well ahead in the polls and he felt that a debate could not help him much but could certainly hurt him, if he did not do well.

For the first time, election returns were gathered and reported cooperatively by the major media through Network Election Service. The N.E.S. was joint enterprise of the Associated Press, United Press International, and the three television networks. It employed a man or a woman in 130,000 of the nation’s 172,500 voting precincts to speed up the results. Each network, however, developed its own interpretation team in a battle of computers, pollsters, and election interpreters. CBS created a new unit called V.P.A .or Voting Profile Analysis, in collaboration with International Business Machines computers (IBM) and Louis Harris, a political pollster. On November 4, CBS was declared the clear winner of election night coverage. Using the V.P.A. system, CBS was able to be the first declare the president around 9:04 p.m. on the basis of electoral vote projection and the use of analytical research. As laid out by the Los Angeles Times, NBC won in the ratings but CBS was considered the superior broadcast, because of the greater visual appeal and the clever use of its election boards and Louis Harris’s predictions.

|

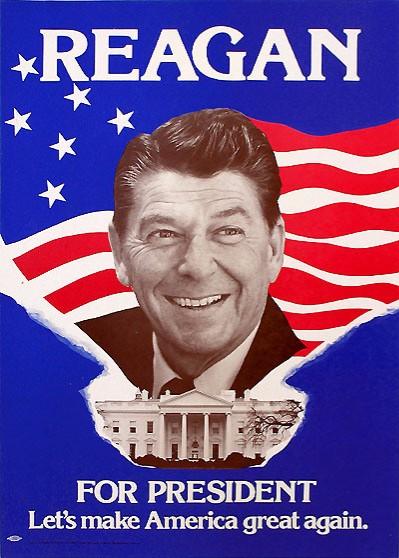

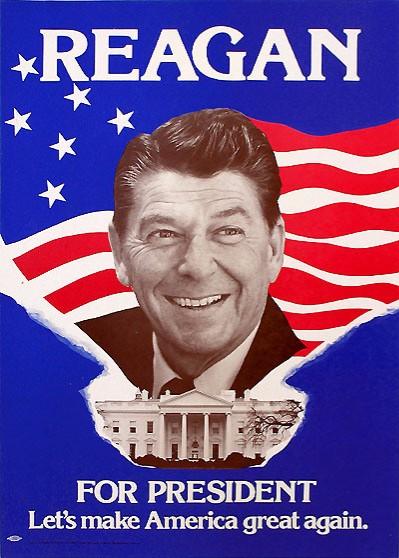

1980 Election Poster for Ronald Reagan.

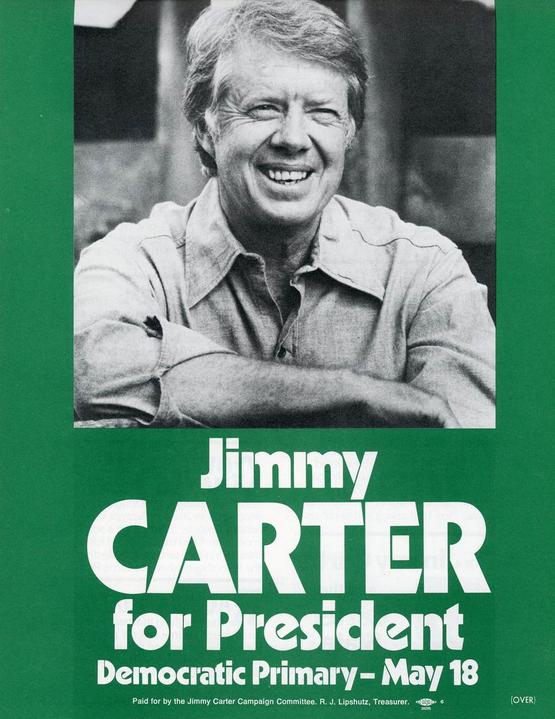

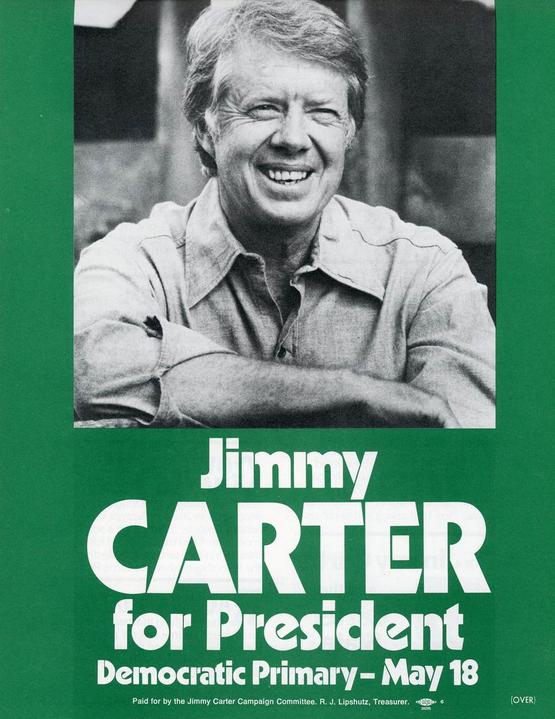

The 1980 presidential election pitted incumbent Democrat Jimmy Carter against his Republican opponent, Ronald Reagan, as well as Republican Congressman John B. Anderson, who ran as an independent. Reagan won in a landslide, and in 1982 the Republicans took control of the United States Senate for the first time in twenty-eight years, marking the beginning of what is popularly called the "Reagan Revolution."

After crowded Republican primaries with seven candidates, the race centered around former Hollywood actor and two-time Californian governor Ronald Reaganand George H. W. Bush, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency and chairman of the Republican National Committee. The contest was tense, with Bush accusing Reagan of “voodoo economics” that promised to increase federal revenue by lowering taxes. Reagan eventually won forty-four contests and arrived at the Republican National Convention in Detroit, Michigan, with 59.8 percent of the primary votes. Although many Republicans found his message too simplistic and his platform too vague and too conservative, Reagan was easily nominated with 97 percent of the vote and picked George H. W. Bush as his vice presidential nominee.

Most incumbent presidents are easily re-nominated by their party, but Carter faced fierce opposition. His administration struggled to improve the economy, and his standing in the poll plummeted in 1978. His main opponent, Senator Ted Kennedy, the last surviving brother of the late President John F. Kennedy, capitalized on these problems, but he had his own difficulties. His involvement in the fatal incident at Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts (when the car he was driving ran off a bridge, killing a woman passenger), as well as his rambling answer to Roger Mudd’s question “Senator, why do you want to be president?” caused voters to have doubts about him. Kennedy struggled to catch Carter, especially as the latter was initially helped by the Iran hostage crisis as the country rallied around the president who vowed to bring the hostages back home. Although he did not have enough delegates to win, Kennedy tried, unsuccessfully, to “open” it and to get delegates released from their voting commitments in an attempt to win the nomination. Carter won the nomination with 63 percent of the vote, against 34 percent for Kennedy at a fractious Democratic convention in New York City. It took several roll calls to conclude the first ballot for the election of the vce presidential nominee, Walter Mondale, and it was the last time during the twentieth century that the Democratic Party had a roll call for the vice presidential spot.

Although the country was plagued by many problems—double-digit inflation, rising unemployment, the crisis in Iran, the Cold War with the Soviet Union—the two candidate attacked each other and proposed few solutions. Reagan campaigned against the Communist threat and "big government" without ever laying out a clear plan on how to address the country's economic woes beyond calling for a massive cut in income taxes. Carter, on the other hand, painted his opponent as an extremist who would divide the nation and might be reckless when dealing with foreign affairs. The two camps had extensive negotiations about holding a debate, and they finally met a week before the election. For many observers, Carter won on substance, but Reagan had better poise and was able to dispel fears that he was the "dangerous" fanatic Carter portrayed. As the Iran hostage crisis dragged on, Carter appeared weak and powerless and lost ground to Reagan in the polls.

There were two debates in the fall of 1980. The first one pitted Independent candidate John Anderson against Ronald Reagan, who was declared the winner. Reagan then debated the sitting President Carter on October 28, 1980. Carter's tactic was to attack his opponent from the start, and he managed to dramatize his differences with Reagan. The Republican candidate, however, managed to present a moderate, upbeat image. He had the best lines, for example when he quipped, "There you go again," when Carter accused him of wanting to cut Medicare and asked in his closing remarks "Are you better off than you were four years ago?" Carter, who had been slightly ahead of Reagan in the polls before the debate, lost ground quickly afterward.

The result was a landslide victory for Ronald Reagan, at sixty-nine, the oldest president to be elected. Although he won just over 50 percent of the vote (Carter captured 41 percent and Anderson finished with 7 percent), Reagan achieved a dramatic victory with electoral votes: 489 to 49. Carter became the first elected incumbent to be defeated for reelection as president since 1932, when Herbert Hoover lost to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

By 1982 , however, President Reagan had grown increasingly unpopular due to a deepening recession that began on July 1981 as a results of the Federal Reserve's contradictory monetary policy, which sought to rein in high inflation as well the stagflation that began to afflict the country in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis and the 1979 energy crisis. The Democrats gained twenty-seven seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, cementing their majority in that chamber at 243 against 192 seats for the Republicans. They only gained one seat in the Senate, which remained in the hands of Republicans with fifty-four seats against forty-six for Democrats.

Television Coverage

Networks geared up early for the primarie,s following closely the candidates who campaigned extensively. After the early caucuses in Iowa and Maine, New Hampshire was the first primary where voters chose a candidate directly among the seven Republican and three Democratic presidential hopefuls. The media then geared up for the conventions: the Republican one took place in Detroit, Michigan, from July 14 to 17, and the Democratic convention followed in Madison Square Garden in New York City from August 11 to 14. The conventions were the most competitive programs for networks, a chance to showcase their talents and increase or consolidate their journalistic credibility.

As was customary, The CBS Election team put together anextensive handbook with all relevant information, from procedural rules and delegate profiles to the efforts by conservative Republicans to find and get a like-minded candidate nominated. There were reportedly four times as many reporters as delegates at the RNC, 11,000 according to convention officials. The main question was who would be Reagan’s choice for vice president. On the convention floor, Dan Rather, Harry Reasoner, Ed Bradley, Lesley Stahl, and Morton Dean as well Bruce Morton, Bob Schieffer, Diane Sawyer, and Susan Spencer all hustled to get information. Mike Wallace landed an interview with both Ronald and Nancy Reagan for 60 Minutes.

The Los Angeles Times printed that the three networks, ABC, CBS, and NBC, spent most of the night as “a conveyor belt for rumors” about Ford. At 9:55 p.m., Rather announced that Reagan had met most of Ford’s demands, and it appeared that the deal was sealed. He offered, however, cautionary warnings as Ford’s selection as the vice presidential nominee had not been officially confirmed. In the end, negotiations broke down, and Lesley Stahl announced that George H. W. Bush had been chosen. The networks were criticized for influencing events at the convention, something Rather refuted.

If the Republican convention was suspenseful, the Democratic one promised to be as dramatic. Expecting a volatile convention, CBS decided to run Dan Rather’s interview with Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter during the regular 60 Minutes slot on Sunday evening and not as originally planned on the first day, like they did with the Reagan interview. A debate and then subsequent vote was scheduled on a proposed rule, F3C, requiring delegates to vote for the candidate in whose name they were elected. This would go against Teddy Kennedy’s effort to force an “open convention,” where delegates would be asked to vote for the candidate of their choice, not the one chosen in the primaries. The measure passed, and Kennedy issued a brief withdrawal statement. The press judged the convention dull, and so was the television coverage. With both conventions being extremely scripted, networks slowly moved away from a gavel-to-gavel approach, cutting away from large blocks of convention during the afternoons, for example.

On November 4, 1980, Walter Cronkite sat for his last anchoring of a presidential election with Harry Reasoner, responsible for the East; Dan Rather, the Midwest; Bob Schieffer, the South; and Lesley Stahl, the West, as well as Bill Moyers, Jeff Greenfield, and J. Kilpatrick. After two years of preparation and $20 million in spending, the networks concluded campaign 1980 within two hours with the sweeping victory of Ronald Reagan. As early as 7 p.m. Eastern Time, exit polls pointed to a Reagan victory. At 9:01 p.m. President Carter telephoned Reagan, and an hour later he gave the earliest concession speech by a presidential candidate since 1904. Political leaders in the West criticized the president, arguing that thousands did not bother to go and vote after his concession speech.

|

Clinton-Gore poster for the 1992 election.

On November 3, 1992, Democrat Bill Clinton defeated incumbent Republican president George H. W. Bush with 43 percent of the vote. Independent Texas businessman Ross Perot secured the highest percentage of any third-party candidate in a U.S. presidential election in eighty years, winning nearly 19 percent of the vote.

Incumbent presidents usually do not face opposition from their own party, but in 1992 the economy was in recession, and Bush had reneged his 1988 promise not to raise taxes in an attempt to curb a soaring budget deficit. He faced a stiff early challenge from Pat Buchanan when the conservative commentator captured nearly 37 percent of the vote in the New Hampshire primary. Although Bush went on to win the Republican nomination, his campaign had suffered.

On the Democratic side the primary season was long and eventful, with former California governor Jerry Brown, former Massachusetts senator Paul Tsongas, and sitting governor of Arkansas Bill Clinton wooing the voters. After news of his alleged twelve-year affair with Gennifer Flowers came out, Clinton’s campaign was nearly derailed. The 60 Minutes interview he and his wife Hillary gave, in which he admitted their marital problems, allowed him to rebound and dominate the Super Tuesday primaries. Despite charges that he dodged the draft and was unfaithful to his wife, Clinton secured the Democratic nomination at the convention in New York and choose Tennessee Senator Al Gore as his running mate. Gore was perceived to be strong on family values and environmental issues, and the team positioned itself as centrists, “New Democrats,” in an effort to avoid charges of being tax-and-spend liberals who were weak on defense.

Seeing two candidates with problems, Texas self-made billionaire Ross Perot saw a chance as a third-party candidate. After supporters filed petitions enabling him to be on the ballot in all fifty states, Perot earned early enthusiastic support, particularly among voters dissatisfied with traditional party politics. Although polls showed him leading both Clinton and Bush, he unexpectedly dropped from the race on the eve of the Democratic convention in July. He came back on the campaign trail in September with former admiral James Stockdale as his vice presidential running mate. Spending $65 million of his own money, Perot led a non-traditional campaign, which ran on opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), elimination of the trade deficit, and national debts. He rarely gave stump speeches and instead used thirty-minute infomercial-style advertisements.

With his middle-of-the road approach and his empathy for the plight of struggling Americans at a time when Bush appeared out of touch, Clinton won 43 percent of the vote and a dramatic 370 electoral votes against 168 for Bush. The Republican candidate had alienated his conservative base by breaking his 1988 campaign pledge against raising taxes. In addition, the economy was in a recession, and foreign policy, Bush's perceived greatest strength, did not play a big role in the campaign following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the 1994 midterm elections, members of the Republican Party captured majorities in the House of Representatives, Senate, and governors' mansions in what was called the Republican Revolution. Members of the Republican party had released a document called the “Contract with America,” in which they detailed what they would do if they were to take the House. The document was the brain child of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, and it also used passages and ideas from former President Ronald Reagan's 1985 State of the Union Address. It laid out many of the conservative movement's ideas such as shrinking the size of government, promoting lower taxes and greater entrepreneurial activity, and advocated both tort reform and welfare reform. Most importantly, it turned the midterm elections, often seen as “local” elections, into a national referendum by promising a major reform of the country’s politics.

The Republican Party won control of both the House and the Senate and was able to pass conservative legislation such as the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, and the Defense of Marriage Act. This victory also contributed to the defeat of Clinton’s health care plan.

Television Coverage

After the 1988 election, a soul-searching process started among news organizations as many felt that the media had not done a good job of informing the public. They had focused too much on the “horse race” and superficial issues such as style and had been too easily manipulated by staged events of the 1998 campaign, such as George H. W. Bush’s visit to three American flag factories.

Late in 1991, the four major television news organizations, ABC, CBS, NBC, and CNN, started to plan for more serious coverage of the 1992 campaign. They wanted to focus on a new format for debates, offer more analytical reporting on issues, and regularly scrutinize political commercials. In an effort to cut costs, networks considered not covering both conventions and, for the first time, pooling voter information on primary nights and using a new organization called Voter Research and Survey. They also reduced coverage of the daily political coverage, using instead materials provided by C-SPAN a well as well collaborating with local stations, instead of sending their own crews. Instead of wasting time and money on the campaign trail, the networks could now use shared videotapes and do more research on the candidates’ positions. Things did not pan out that way.

The candidates themselves changed the way they campaigned, skirting the news media and addressing their message directly to the voters. They adjusted to the technological revolution of the 1980s, with video cassette recorders, cable television, and personal computers, but also to the fact that audiences had become used to getting information not from centralized sources but from a multitude of sources. As a response, candidates used of interactive 800 numbers and computers and were able to organize electronic town meetings via satellites. Instead of TV news shows, candidates appeared on TV talk shows such as the Phil Donahue Show, where Jerry Brown and Bill Clinton faced off in the primary, or Larry King Live, where Ross Perrot announced his candidacy. Such shows allowed ordinary citizens to call in and audience members to directly ask questions to the candidates. This “unfiltered” access to candidates, a new form of electoral participation, did not, however, lead to more openness or clarity in terms of issues, as candidates sought out programs with the best chance of getting easy questions.

The networks contributed to this focus on image and style. On the evening news, they used soundbites—clips of presidential contenders speaking—that went from 42.3 seconds in 1968 to 9.3 seconds twenty years later, and was a mere 7.3 seconds in 1992. At a forum sponsored by the Joan Shorenstein Barone Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, top network anchors sharply criticized their own campaign reporting. Rather said that campaign reporters had shown a “lack of guts,” and Peter Jennings explained that the news media pledge of better coverage was “derailed” by the Gennifer Flowers episode. PBS's Jim Lehrer worried that the news media were losing credibility. From Tom Brokaw to Peter Jennings, all had to deal with the fact that “serious” political reporting is often dull, a difficult things in an age of exacerbated competition.

15,000 journalists attended the Democratic National Convention in Madison Square Garden in New York without a clear story to report on. The Clinton-Gore ticket had already been announced, and the only suspense was over whether Jerry Brown would be allowed to speak and if Jesse Jackson would endorse and support Clinton. Both Jennings and Rather anchored from the convention floor for their ninety-minute coverage, which started at 10 p.m., missing, for example, Jesse Jackson's much-anticipated speech on the first day. The convention was described as dull, and, in the face of dwindling ratings, Reuven Frank, former president of NBC News, suggested that networks should stop covering them, something Rather adamantly refuted in an op-ed in the New York Times. The CBS anchor argued that “It is incumbent on us to air the positions and views of the major parties in a responsible and thorough manner; covering convention is one way we do that.” Even if conventions are “uneventful, unhelpful and unwatched,” Rather was of the opinion that broadcasting them is “good citizenship, good public service.” All networks, however, devoted less than half the time to the convention as they did in 1988. The highlight of the Republican National Convention in Houston was President Reagan’s speech; the Washington Post described Pat Buchanan’s speech as a “hate-filled harangue.” As Elizabeth Glaser had done at the Democratic convention, Mary Fisher's speech on AIDS at the Republican convention helped raise consciousness about the virus and the plight of people infected. Bush delivered a speech that was not seen as the networks only signed on at 9:30 p.m. For CBS, Rather was on the floor with Ed Bradley, Connie Chung, and Bob Schieffer, while Charles Kuralt was in the booth.

In the fall of 1992, preparations started for the debates between Bush, Clinton, and Perot, which were sponsored by the bipartisan Commission on Presidential Debates. The Clinton campaign agreed that the commission should choose the panelists, but the Bush team insisted on veto power over questioners, as was done in 1988. This raised ethical questions, and several journalists and news organizations announced they would not participate. In the end, the parties decided on a nine-day marathon with three presidential debates on October 11, 15, and 19, respectively, and one vice presidential debate on October 13. In the final weeks of the campaign, Clinton held a persistent lead over President Bush, and the debates were Bush's last opportunity to catch his Democratic opponent. CBS News was unable to carry the first debate in St. Louis as the network was broadcasting the Major League Baseball playoffs. The debates drew large television audiences, as many as 90 million viewers, but Dan Rather refused to call them debates, preferring “joint appearances” and “happenings.”

Clinton’s lead in the polls remained significant, and on election night networks were attempting to observe the gentlemen’s agreement not to reveal survey results from each state until that state’s polls had closed. As the coverage began at 7 p.m., exit polls already showed that Clinton would be elected, but anchors and correspondents continued to urge people to vote. They declared Clinton the winner at 10 p.m., and twenty minutes later George H. W. Bush gave his concession speech. Dan Rather anchored the CBS News coverage with Bob Schieffer on the U.S, Senate, and Connie Chung, Mike Wallace, Charles Kuralt, and Ed Bradley following the major issues of the 1992 elections.

Wondering why the 1994 elections were not more extensively covered, the Washington Post praised CBS News for its coverage, adding that the network had “ the most and the best, with Dan Rather back in the driver’s seat and the ablest supporting team in town.” Ton Shales singled out Dan Rather who showed "the most enthusiasm, the most finesses and the most delight.”

|

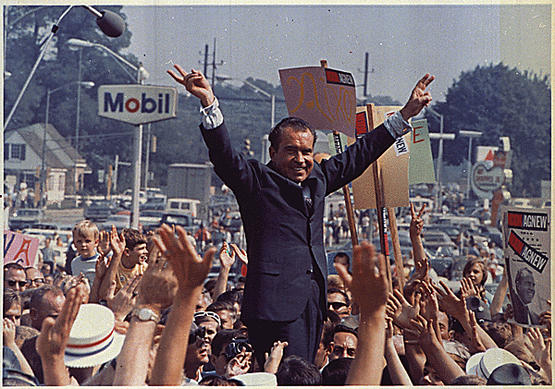

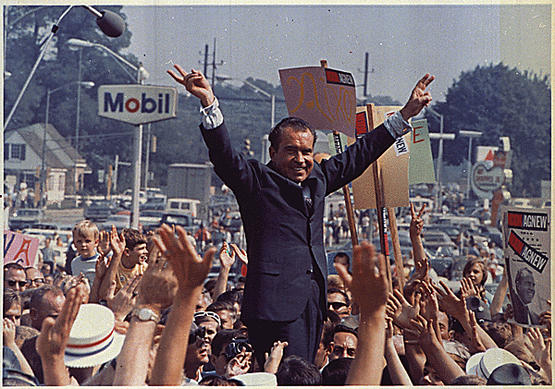

Richard M. Nixon 1968 Presidential Election Campaign. Oliver F. Atkins—White House Photo/Nixon Presidential Library and Museum/NARA.

The presidential election of 1968 was one of the most chaotic in American history.

As a sitting president, President Lyndon Johnson was the front-runner for the Democratic nomination. However, growing opposition to the war in Vietnam, unrest on college campuses, and urban rioting made him vulnerable. With the end of the Vietnam War as his central issue, Minnesota’s Democratic Senator Eugene J. McCarthy announced his candidacy in November 1967. He mobilized hundreds of student volunteers, who went "clean for Gene," cutting their hair and campaigning for him in New Hampshire. McCarthy won 42 percent of the vote in March 1968 and, more importantly, twenty of the twenty-four delegates. His shocking success motivated Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York to enter the race for the Democratic nomination shortly thereafter. With approval ratings at their lowest as antiwar protests surged, Johnson announced in April 1968 that he was not running for reelection.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey then entered the race, but it was too late to run in the primaries. His only path to nomination was to win delegate support at the nominating convention in Chicago that summer. In the meantime, Kennedy quickly gained immense popularity in the race, and was, after winning California, within reach of securing the Democratic nomination. His assassination by Sirhan Sirhan, an Arab nationalist angry about Kennedy's support of Israel, cut everything short. His death, just a few months after Martin Luther king Jr.’s assassination, increased the sense of fear and instability in the country.

Many Democrats turned to the seasoned Humphrey, who by late August controlled the majority of delegates at the Democratic Convention in Chicago. Humphrey had been a supporter of Johnson’s Vietnam policies and thousand demonstrators descended on Chicago with one common goal: pressuring delegates to end the war in Vietnam and change the political system. Amid oppressively hot and humid weather, conditions in Chicago were ripe for a disaster: air conditioning, elevators, and phones were operating erratically at the convention; taxis were on strike; the National Guard had been mobilized and ordered to shoot to kill, if necessary. Chaos ensued both outside in the convention hall, where protestors were clubbed to the ground by the Chicago police, and inside, where the proceedings were at times out of control with shouting matches between delegates.

In the end, Humphrey received the nomination from an embattled party and choose Edmund Muskie as his running mate. But the damages were long lasting: many lost faith in politicians, in the political system, in the country, and in its institutions. Supporters of McCarthy and McGovern, who had rallied Kennedy's supporters around him, were left with a sense that the bosses, not the people who voted in the primaries, decided who the nominee should be. The discussion about ‘superdelegates” who have the final say in elections continues to this day. In the wake of the convention, the Democratic National Committee set up a McGovern Commission that put forth guidelines for the selection of delegates. They opened the party’s deliberations to more young people, to African Americans, and to women.

The Republican nominating contest was orderly compared to the Democratic one. Richard M. Nixon swept the Republican primaries and easily won the nomination at the Republican convention against opponents such as Michigan governor George Romney and New York governor Nelson Rockefeller. Nixon ran as the champion of the "silent majority," those who rejected the radicalism and cultural liberalism of the time. He chose the conservative and relatively inexperienced governor of Maryland, Spiro Agnew, as his running mate, partly to appeal to Southern conservatives. A move even more important, as Alabama Governor George Wallace had entered the election as a third-party candidate for the American Independent Party, running on a platform of extreme social conservatism. Wallace railed against “pointy-head intellectuals” and anarchists and for “law and order,” and stood, throughout the campaign, at 20 percent in the polls.

During the general election campaign, Humphrey initially struggled but eventually came back with the help of his running mate Muskie and his pledge, if elected, to stop bombing North Vietnam as “an acceptable risk for peace.” Nixon had a breezy campaign, leading in the polls during most of the general election; so much that he could take the weekend off to rest. A series of televised interviews in October, however, got him into hot water, while Humphrey received McCarthy's support. President Johnson’s announcement that he would suspend air attacks on North Vietnam helped Humphrey close some ground. His last minute surge, however, came too late. On Election Day the popular vote was close: Nixon had 43.4 percent, Humphrey had 42.7 percent, and Wallace won 13.5 percent of the popular vote. But Nixon's Electoral College margin was substantial, 301 to 191 to 46. Despite the closeness of Nixon's victory, it was a resounding mandate against Johnson and the Democratic Party.

Despite heavy campaigning by Vice President Spiro Agnew and Nixon himself during the 1970 midterm elections, the Democrats retained their Senate majority of fifty-four against forty-three for the Republicans, despite losing a net of three seats. The Republicans and the Conservative Party of New York picked up one net seat each, and former Democrat Harry F. Byrd, Jr. was re-elected as an independent. They also increased their majority in the House, picking twelve seats for a balance of 253 against 192 for the Republicans. The increasing fatigue over the ongoing Vietnam War as well as the fallout over the Kent State Massacre are often cited as reason for the Democrats' gains.

Television Coverage

After a stint in Vietnam, Rather resumed his post as White House correspondent in 1966. He played a bigger role in CBS coverage of the 1968 election, covering the two conventions. In Chicago, he was punched in the stomach by security guard as he attempted to question a delegate being escorted out. The scene aired live on TV, prompting Cronkite to exclaim " We have a bunch of thugs here." On election night, Rather was responsible for the Midwest, next to Roger Mudd (South), Mike Wallace (East), and Joe Benti (South). Cronkite anchored the evening, and Eric Severeid offered commentary.

Rather had closely followed the primaries, reporting on them for the CBS Evening News, but also in his radio reports in the series First Line Reports. His brief reports, usually from Washington and less than five minutes long, gave him more freedom in tone and range of topics. From the fall of 1967 on, he speculated on whether Johnson would run or not , introduced listeners to McCarthy after he announced his candidacy, pondered over Kennedy’s decision to run, and analyzed McCarthy's early wins. Rather was on air with Roger Mudd when Johnson announced that he would not seek re-election, a news that took both reporters by surprise and they tried to make sense of it, live on the air.

As candidates made a case for their nomination, one of the major topics to emerge was the issue of televised debate and the “Fairness Doctrine,” which was designed to protect all factions by providing equal airtime on television according to Section 315 of the Communication Act. It became problematic in 1968 when the presumed candidate, Johnson, was also the current president. The Federal Communications Commission tried to distinguish between an appearance as “President of all the people” and his programs as a “candidate.” Network and influential newspapers were pushing for a televised debate before the convention, but the equal time provision led to “migraine” as explained by Variety. As early as May 1968, the network devised a plan presented by CBS News's Franck Stanton to organize political debate with the republican and democratic candidates as well as George Wallace. The plan hinged on congressional approval and the suspension of the equal time provision of the FCC. Networks would otherwise have to give equal time to a number of minor parties, an estimated half-dozen in 1968, as well as the major party candidates.

In May 1968, the Senate commerce committee unanimously approved a resolution to clear the way for televised debates among major presidential candidates, leaving it up to the networks to include or not George Wallace and his American Independent Party. By September, the House commerce committee was scheduled to vote to suspend equal time rule. Although neither Nixon nor Humphrey were originally willing to give Wallace equal billing, the Democratic candidate agreed to a debate, partly as a way to rally Democratic voters. Nixon, who had faired badly against Kennedy in 1960, decided not to participate, something Humphrey used in the campaign.

Building on their successful 1964 and 1966 coverage, networks geared up with an arsenal of computers (RCA SPECTRA 70/45 FOR NBC, IMB System/360s for ABC and CBS). The competition among candidates was as tight one among networks, as the later all hoped to increase sales if declared winners. Among its novelties, CBS used IBM 2250 display units to post results electronically and built a new set, a two-story high circular information center. As predicted, the night was very long, with seventeen hours of continuous coverage, from 6 p.m. to 11 a.m. It was, as Broadcasting put it “the most expensive, extensive and apparently closely watched” election yet, with an estimated 142 million people in the United States. It was found out afterward that the main reason Nixon was not declared the winner several hours earlier was because of an unexpected programming error that forced NES to switch to its backup system.

Just a days after the election, Cronkite sat with the regional correspondents to discuss 'What Happened Last Night."

|

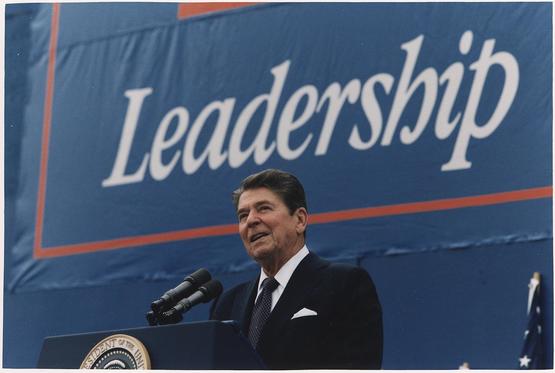

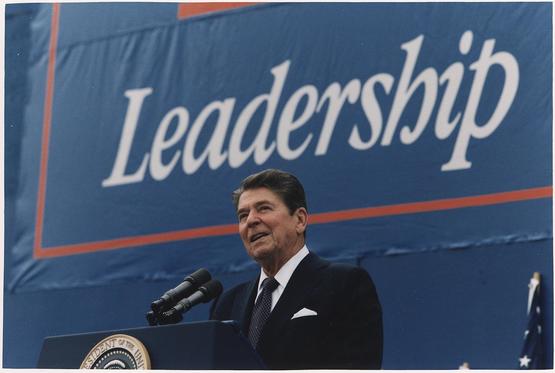

Photograph of President Reagan giving campaign speech in Texas, July 24, 1984. Courtesy of the National Archives.

On November 6, 1984, Republican Ronald Reagan was elected to a second term in one of the biggest landslides in U.S. election history. He defeated former vice president Walter Mondale. Democratic nominee Mondale had chosen Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate, the first time a major party had a woman on its ticket.

Reagan faced no opposition in the primaries and was easily renominated by the Republican Party. The field was more crowded on the Democratic side. Out of the eight initial candidates, three remained in the race: the African American preacher and civil rights activist Jesse Jackson, incumbent senator Gary Hart of Colorado, and former senator and vice president Walter Mondale. Mondale eventually won the nomination and made history by choosing as his running mate Geraldine Ferraro, a three-term congresswoman from New York.

The Democratic ticket could never find an issue to rally voters against Reagan, who represented for many voters leadership, patriotism, and optimism. Neither the increasing gap between rich and poor, the alleged misbehavior by Reagan aides during the Iran-Contra affair, nor Reagan’s close ties with aggressive fundamentalist groups could make a dent in the reputation of the man his detractors called the “Teflon President” and his supporters referred to as “the Great Communicator.” Reagan’s poor performance in two of the televised debates did not diminish his lead in the polls.

On election day, Reagan won by 17 million popular votes and an electoral landslide of 525–13, the second largest electoral victory in history.

Two years later, Republicans faced tough midterm elections. Although Reagan himself was still relatively popular, the president's party, as is often the case in midterm elections, lost seats. Winning a net gain of eights seats, the Democrats were able to recapture control of the Senate for the first time since 1980 with a fifty-five to forty-five balance. They also managed to cement their majority in the House, where they gained five additional seats, bringing the balance to 258–177.

Television Coverage

The 1984 elections came three years after Dan Rather replaced Walter Cronkite as anchor of the CBS Evening News. After a rocky start, Rather found his bearings and had been leading in the ratings against ABC’s Peter Jennings and NBC’s Tom Brokaw. Presidential elections were always a time of heightened competition among the networks, and 1984 was no exception. It was the first presidential election that Dan Rather, Tom Brokaw, and Peter Jennings anchored, and the stakes were high for the newly-minted anchors.

With Reagan's renomination a given, the media focused more heavily on the Democratic primaries, where everyone expected Mondale to win the early primaries. Gary Hart's victory in New Hampshire, however, changed everything, “a first-class upset.” He and Jesse Jackson, the second African American to launch a nationwide presidential campaign, proved to be surprising opponents. While they welcomed the unexpected suspense, the networks were markedly more cautious in calling races before most of the polls were closed during the primaries, a response to sharp criticisms about the use of exit polls during the 1980 election. Eleven debates were organized during the Democratic primaries with, among others, ABC’s Barbara Walters, NBC’s John Chancellor, as well as Ted Koppel and Phil Donahue as moderators.

On March 28, 1984, the eighth Democratic presidential debate was moderated by Dan Rather, produced by Joan Richman, and directed by Artie Bloom at Columbia University. Hoping “not to get pat answers, not to get pre-packaged response . . . have meaningful straight talk,” CBS used a different stage for the debate: candidates and moderator were seated at a round table, with Hart and Mondale sitting directly across from each other and Jackson face to face with Rather. Eight cameras were used to capture the event from many angles. The Washington Post described Rather’s questions as “sharp, fresh and conductive to good answers. His first was a doozie: he asked each candidate to confess his “main weakness . . . as a person.” The debate was marked by sharp exchanges between Hart and Mondale, making Jackson and even Rather look more presidential.

For the 1984 conventions, the three networks decided to move away from a gavel-to-gavel coverage, which only a handful of viewers tuned in to anyway, and offered instead a two-hours-a-day summary. Only CNN, C-SPAN, and PBS stayed with the convention throughout the day. This led to politicians scrambling to ensure that their speeches would be aired during prime time. During the 1984 Democratic National Convention, held at the Moscone Center in San Francisco, California, from July 16 to July 19, 1984, three of these speeches stood out: New York Mayor Mario Cuomo’s “Tales of Two Cities,” and vice presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro’s acceptance speech. But it was Jesse Jackson’s “Our Time Has Come” speech that triggered the most reactions. Described as “incandescent,” it was clear to most that it was an enormously powerful moment, celebrating the very possibility of an African American presidential candidate.

The 1984 National Republican Convention convened from August 20 to August 23, 1984, at Dallas Convention Center in Texas. As Reagan's nomination was unchallenged, the convention was judged by most as being quite dull. The main and only controversy revolved around whether or not networks should air the “Reagan film,” an eighteen-minute film used to introduce the president. Considering it a commercial and not hard news, ABC and CBS decided against airing it. Instead, they presented on-air discussions on the issues and their decision, showing excerpts from the Reagan's and the Mondale's film to make their points. In the absence of any hard news coming from the convention, NBC, as well as C-SPAN and CNN, decided that the airing of the film itself had become the news, and they showed it.

CBS News and Rather looked “strong” in their coverage of the conventions, according to the Washington Post, and Rather worked well with the floor correspondents Ed Bradley, Lesley Stahl, Bob Schieffer, and, for the first time, Diane Sawyer, as well Eric Engberg, Bob Faw, and Susan Spencer. During the Republican convention, Rather interviewed Vice President George Bush and First Lady Nancy Reagan. He was joined by Bill Moyers for “the most trenchant and accessible analysis of the conservative takeover” of the Republican Party. According to Tom Shales, “this conversation between Moyers and Rather was a dramatic reassertion of the depth and strength of the CBS team. This wasn’t just tossing the latest floor gossip or restating voguish truisms. Moyers was superb.”

Reagan and Mondale debated each other twice in the fall of 1984, on October 7, 1984, and October 21, 1984, while Vice President George H. W. Busch debated Democratic contender Geraldine Ferraro once on October 11, 1984. All three debates were sponsored by the League of Women Voters, which submitted 103 names of journalists before the candidates could find three they could agree on. The first debate was moderated by Barbara Walters of ABC News, with James Wieghart of the New York Daily News, Diane Sawyer of CBS News, and Fred Barnes of the Baltimore Sun as panelists. The focus was on economic and domestic issues. Behind in the polls, Mondale’s plan was to go on the offensive from the start while Reagan, much like he did in 1980 against Carter, planned to “stay above the fray.” The debate was marked by biting attacks and clashes about the federal deficit and the economy, as well as about abortion and the relationship between government and religion. Reagan declared that the country was better off than when he took office, while Mondale argued that huge budget deficits threaten the economy. The Democratic candidate repeatedly accused Reagan of damaging the Social Security and Medicare programs. Both men stood their ground, and the debate did not appear to sway any voters. Reagan’s performance, however, was subpar, with the president rambling at some points and seeming tired, giving rise to a torrent of stories regarding his age. The question of age came up in the the second debate, which focused on defense and foreign policy issues and was moderated by Edwin Newman of NBC News, with Georgie Anne Geyer from the Universal Press Syndicate, Marvin Kalb from NBC News, Morton Kondracke from the New Republic as panelists. Reagan was prepared, and he delivered one of the most memorable lines in the history of American presidential debates “I will not make age an issue. I will not exploit my opponent’s youth and inexperience." Although Mondale performed strongly in both debates, a strong economy and a renewed sense of strength on the international stage secured Reagan's victory.

As the campaign advanced, CBS changed its angle. While the network had earlier decided not to include events that did not advance the story of the campaign, “pieces in which a candidate said nothing new would not go on the air,” it reversed course two weeks before election night. Speeches of candidates would be given air time, and the network would focus on the “horse race” aspect of the election. In addition, as Broadcasting notes, the CBS Evening News with Dan Rather devoted as much as a fourth of its time to political news, covering everything from regional political strategies, to polling results. The candidates themselves gave a last-minute media push, buying fifteen- and thirty-minute periods on ABC, CBS, and NBC, as well as thirty-second spots. On election eve, however, Reagan’s lead over Mondale was wide and seemingly insurmountable.

Campaign 1984 was a major election year, with the election of not only the president but also one-third of the Senate and all 435 members of the House, plus thousands of state and local officials. The networks geared up for the evening, spending an estimated $20 million. For CBS News, Rather anchored the coverage from New York with Bruce Morton reporting on the presidential race, Bob Schieffer on Senate races, Lesley Stahl on the House races, as well as Bill Plante and Susan Spencer reporting from the Republican and Democratic headquarters. Bill Moyers provided analysis and commentary while Diane Sawyer reported on special interest groups such as labor, women, minorities, and religious groups. The networks anticipated confrontation with Congress, which had adopted a resolution calling “all broadcasters and other members of the media” to voluntarily “refrain from characterizing (project a trend) or projecting results,” arguing that these practices influenced voters. All networks pledged to work in that direction. Reagan’s victory, however, became obvious very early on election day. CBS declared him the “projected” winner at 5 p.m. with 3 percent of the vote tallies in and polls in twenty-six states still open. At 8:01 p.m., Reagan was officially declared the winner. The rest of the night was spent seeing how big Reagan’s victory would be. Rather also repeatedly urged viewers to vote in local and regional races: “there is still a lot at stake.” Lesley Stahl explained that “the real drama” was in the contest for the House, where the Republicans were hoping to gain twenty-six votes to regain the majority.

CBS received high scores for his coverage, especially the commentary of Bill Moyers. Dan Rather, who had a sore throat virus, was nevertheless described by the Los Angeles Times has being “wired as a fox terrier.”

For the 1986 midterm elections, CBS and Dan Rather decided to stay "wall-to-wall" with the elections, from 7 p.m. to almost 2 a.m. Eastern Time. Noting that "There's no denying that Mr. Rather gets excited about elections like no other anchor," the New York Times described CBS's coverage as "zippy, sometimes even dizzy," and Rather as "particularly unbuttoned and relaxed." For the Washington Post, CBS's scoverage was "gripping, colorful, eventful," with "bright, data-packed and lit like a forest full of Christmas trees." Both papers thanked the network for staying with the elections through the night, something that all networks "once considered proper civic behavior."

|

President William J. Clinton and Vice President Al Gore, January 20, 1997. Courtesy of the National Archives.

On November 5, 1996, Democrat Bill Clinton was elected to a second term, defeating Republican Bob Dole, a former U.S. senator from Kansas and Republican leader of the United State Senate.

As a sitting president, Clinton was easily nominated as the Democratic candidate during the Democratic National Convention, which took place in Chicago, Illinois, between August 26 and 29, 1996. The field was crowded on the Republican side with Bob Dole, conservative commentator Pat Buchanan, businessman Steve Forbes, former Tennessee governor and U.S. secretary of education Lamar Alexander, and conservative commentator and former diplomat Alan Keyes. Dole eventually prevailed and captured the Republican nomination. He resigned from the U.S. Senate to focus on his campaign and selected as his vice presidential running mate Jack Kemp, a former congressman from Buffalo, New York, who was highly regarded in conservative circles for his views on taxes.

Two years into his presidency, Clinton was somewhat struggling in terms of popularity because of his failed healthcare reform initiative, his federal assault weapon ban, and his proposal for allowing gay men and lesbians to serve openly in the military. While the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” compromise was eventually secured, the president was considered by many pundits to be in a weak position. Under the leadership of House Speaker Newt Gingrich, however, Republicans in Congress had pursued policies in an uncompromising and confrontational manner, forcing two partial government shutdowns in 1995 and 1996 over funding for Medicare, education, the environment, and public health. During these tense times, Clinton’s moderate approach won him a lot of public support. Third parties included the Libertarian Party, the Natural Law Party, the U.S. Taxpayers' Party, and the Reform Party which nominated Ross Perot as its candidate. Unlike the 1992 campaign, the Texas businessman received less media attention and was excluded from the presidential debates. He nonetheless obtained substantial results for a third-party candidate by U.S. standards, with 8 percent of the popular vote.

With a recovering and increasingly strong economy and stable international affairs, Clinton kept his two-digit lead in the polls over Dole throughout the campaign. Democrats’ tactics during the campaign included associating Dole with the unpopular Newt Gingrich and blasting Dole’s proposed tax cuts at a time when progress was being made to cut the deficit. They also played on Dole’s age, a point that impacted some voters, especially after the seventy-three-year-old fell onstage at a campaign event and inadvertently referred to the "Brooklyn Dodgers," who had moved to Los Angeles three decades earlier.

In November, Clinton captured 49 percent to Dole’s 41 percent and Perot’s 8 percent. In the electoral college, Clinton won 379 votes to Dole’s 159. Despite Dole's defeat, the Republican Party was able to maintain a majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Television Coverage

As audiences for convention coverage continued to dwindle, from 30 percent on the first night of the Republican convention in 1992 to 23 percent four years later, networks, as James Bennet explained in the New York Times, tried to reconcile several competing needs: “to resist becoming propagandists for the parties, to woo viewers with compelling images and to present a fair picture of the proceedings.” For their part, the GOP planned and executed a 1996 convention “scripted for television,” a four-day infomercial designed to showcase unity and harmony and looked away at any discord or dissent. Set in San Diego, California, from August 12 to 15, the convention was tightly choreographed. In addition to speeches by former presidents Gerald Ford and George H. W. Bush, the RNC staged a series of “emotionally charged moments that no amount of network commentary could neutralize.” Delegates and viewers saw a video tribute to Ronald Reagan, followed by an address by Nancy Reagan. In closing, retired general Colin Powell saluted Reagan’s oversized video image, electrifying the crowds.

The program inevitably led to friction as the networks strived to air only “newsworthy” footage from the convention and complained that they had been misled about the content of the Reagan video, which ABC and NBC decided to air and CBS decided against. They also objected to the fact that the party failed to give them advance copies of the speeches so they could be evaluated. All networks showed an hour of the convention, from 10 to 11 p.m. Eastern time, but, in that time, they only carried between thirty-five and forty-two minutes of the convention planners’ program itself—what took place on the podium. Instead, they interviewed delegates on the floor, including some like Pat Buchanan who had not been allowed to give a speech, talked about the use of technology, and commented on the very choreography of the convention. They pointed, for example, to the discrepancy between the diverse set of speakers on the podium and the overwhelmingly white and male delegates and conservative platform, and laid out the party's internal rift about abortion.

In the absence of real news ahead of the Democratic convention in Chicago, the media focused on the tumultuous 1968 Chicago convention, highlighting the dramatic differences with 1996. They also followed Clinton as he conducted a whistle-stop tour through the heartland abroad “The 21st Century Express,” the campaign slogan of the Democrats being “building a bridge to the 21st century.” The Democratic convention was as scripted as the Republican one, with Aretha Franklin singing the national anthem, Christopher Reeve giving an emotional speech, and the First Lady receiving roaring applause. Only on C-SPAN could viewers see the speeches of Jesse Jackson and Mario Cuomo, which were scheduled in the afternoon, as the networks limited themselves to one hour live in the evening. As schedule changed slightly, networks who covered the events live felt trapped, unable, for example, to cut away from the president for fear of being seen as disrespectful. Networks tried to adapt: CBS, for example, signed on a little earlier to allow time for background and context before Clinton’s speech and refused again to show the official “Clinton movie.” As the convention ended, pundits stated that the 1992 convention coverage was surely the last one of its kind and that the way networks cover campaigns and conventions was bound to change radically.

Two presidential debates were organized on October 6 and 16 between Bill Clinton and Bob Dole, while Al Gore and Jack Kemp faced off on October 9. The debates were without any surprises and were not as dull as expected, with Clinton clearly more at ease during the second debate, a “town meeting” with invited citizens. The debates were symptomatic of a lackluster campaign that Americans were not interested in. On election eve, polls showed Clinton leading Dole 55 to 37 percent.

Preparing for election night, the CBS News team invested in virtual set, 3-D graphics, and a touchscreen. Dan Rather was supposed to push a button on a touchscreen map of the United States while on the air, allowing him to display the latest election returns. In addition, the network posted continuously updated election returns on its World Wide Web site for the first time. Things went smoothly with just a few technological hiccups on election night. The touchscreen map did not always work, and election sites appeared swamped at night, but the new medium worked pretty well, passing something of a milestone. CNN got about 50 million hits, or requests, and CBS estimated it had 10 million hits. In order to beat the competition in calling races, network news operations employed their own statisticians and data analysts to study the results of exit polls provided by the Voter News Service. As was the case for the previous three elections, politicians complained that early predictions would discourage voters in the West. Dan Rather announced that Bill Clinton had been reelected at 9 p.m. Eastern time and continued to urge people to vote.

For the Washington Post, “CBS had the best and certainly the most elaborate graphics, including a three-dimensional 'reality room' for Harry Smith to bounce around in. CBS also had, it hardly needs to be said, the best anchor, the one and only Dan Rather.” The 1996 CBS election team included Ed Bradley, Mike Wallace, Paula Zahn, and Bob Schieffer.

|

President Nixon Greeted by Dwight D. Eisenhower High School Students in Utica, Michigan, August 28, 1972. Courtesy of the Richard Nixon Library.

The 1972 campaign ended in a landslide victory for Republican candidate Richard Nixon. His victory was short-lived, however, as a mere two years later he resigned in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

Richard Nixon's renomination by his party was a foregone conclusion. After his “coronation” at the Republican convention in August 1972, he ran on a campaign that emphasized the economic upswing and his successes in foreign affairs. He pledged to secure “peace with honor” in Vietnam and established relations with China.

On the democratic side, things were almost as chaotic as in 1968.

After the divisive nomination struggle and convention of 1968, the McGovern-Fraser commission was charged in part with making sure that party leaders would not work behind closed doors to manipulate the nomination process. It redesigned the Democratic nomination process and streamlined it so that voters in the primaries would have a direct say on who their nominee for president would be. The fundamental principle of the McGovern-Fraser Commission—that the Democratic primaries should determine the winner of the Democratic nomination—has lasted to the present day. Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts was considered the very early favorite, but the incident at Chappaquiddick in 1969 ended his prospects. Representatives Patsy Mink of Hawaii and Shirley Chisholm of New York announced their candidacies for the Democratic nomination, becoming the first Asian American and black women to run for the office. In the primaries, Senator George McGovern got an early lead over Maine Senator Edmund Muskie, Hubert Humphrey's running mate in 1968, despite opposition from many establishment Democrats.

McGovern was the first to benefit from the changes implemented as a result of the McGovern-Fraser commission. The changes in the primaries meant that party regulars were displaced by a new generation of elected representatives, described by the resentful old guards as "long-haired youths, blacks, Chicanos, and activist women." Although the Democratic National Convention was chaotic, with hundreds of delegates angry at McGovern for various reasons, McGovern became the Democratic Party’s nominee for president in 1972. Choosing a running mate was even more complicated. Senator Edward Kennedy turned down the offer, and McGovern eventually nominated Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton. On the ballot were also former governor Endicott Peabody of Massachusetts, Alaska senator Mike Gravel, state representative Frances Farenthold of Texas, New York City advertising executive Stanley Arnold, Representative Peter Rodino of New Jersey, and Clay Smothers, a journalist from Dallas. Other real and fictional names received votes, including Martha Mitchell, Archie Bunker, Jerry Rubin, and even CBS News correspondent Roger Mudd. Eagleton wasn't declared the winner until 1:51 a.m., and his and McGovern's acceptance speeches didn't begin until well after 2 a.m. Thirteen days later, Eagleton confessed that he had been hospitalized three times in the 1960s for depression and stress, and that he had undergone electric shock therapy. McGovern first insisted that he would not remove Eagleton from the ticket, declaring that he was behind him "1,000 percent." Two weeks later, on July 21, Eagleton withdrew from the ticket under pressure and was replaced by Sargent Shriver, the former director of the Peace Corps and ambassador to France under Johnson and Nixon.

During the general election in the fall of 1972, it became evident that McGovern was too liberal for the majority of American voters. McGovern had said during the campaign, “If I were president, it would take me twenty-four hours and the stroke of a pen to terminate all military operations in Southeast Asia.” He planned on withdrawing all American troops within ninety days of taking office, whether or not U.S. prisoners of war were released. To many Americans, including many Democrats, McGovern’s position was tantamount to total capitulation in Southeast Asia. In the end, McGovern’s campaign was undermined by his own restructuring of the primary process (which alienated many powerful Democrats and reduced his funding support), the perception that his foreign policy was too extreme, and his indecisiveness over choosing a vice presidential running mate. The Nixon campaign successfully portrayed him as a radical left-wing extremist.

Nixon won the election, with a 23.2 percent margin of victory in the popular vote, the fourth largest margin in presidential election history. He received almost 18 million more popular votes than McGovern—the widest margin of any U.S. presidential election. Voters, however. distinguished McGovern from the Democratic Party as a whole. The Democrats widened their majority in Congress and picked up two Senate seats, giving them fifty-six. Despite his overwhelmingly strong position, Richard Nixon had engaged in a variety of dirty tricks during the campaign. These culminated in the botched burglary in the Watergate. The scandal ultimately led to his resignation in 1974, but it had no impact on the 1972 campaign.

During the 1974 midterm elections, Republicans lost seats in both houses of Congress, as a result of the Watergate scandal and Ford's pardon, the energy crisis, and an economy marked by inflation and stagnation, as well as the "six-year itch." Democrats won forty-nine seats in the House of Representatives, increasing their majority above the two-thirds mark (291 to 192) and ended up with a majority of sixty Senate seats against thirty-eight for the Republicans, one seat of the Independent Democrat and one for the Conservative in New York.

Television Coverage

As preparation for the Democratic convention started, it became clear that the stakes were quite high for the networks, especially for CBS News. The network wanted to demonstrate that it was able to surpass NBC during coverage of special events and consolidate its position as the no. 1 news network. The CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite had been winning the race in the previous five years against John Chancellor on NBC and with ABC’s Harry Smith and Harry Reasoner climbing in the ratings. In other words, “supremacy at stake in TV News.”

As described in Broadcasting, the relationship between networks and the political parties improved and cooperation replaced hostility. Networks sent more than 1,400 news professionals and produced mre than forty hours of programming, spending about $20 million. CBS alone spent the most, about $7 million, and anchorman Water Cronkite came with twenty-one correspondents. Unlike in 1968, no newsmen were “arrested or clubbed.” Ahead of the conventions, CBS aired two “What’s a Convention All About?” stories in an effort to elucidate the proceeding of the conventions and put into perspective terms such as platform, bandwagon, etc. Anchored by Walter Cronkite, the program was ostentially for youngsters but designed to provide answers for adults too. CBS also announced the launch of a fourteen-week Sunday series entitled Campaign ’72 in the 6–7 p.m. spot usually reserved for 60 Minutes. Interviewed by TVTV during the Democratic Convention, Rather explained that “I am pretty corny about that, I get excited about conventions. Each one is different for me and I do get excited about it. It’s a hell of a good story even though people say this one is duller that the last one and not as exciting as the 1952 convention, that may be true, but I find it a terrific story. Any time you get this many politicians under one roof, for a reporter, it’s like a kid being turned loose in that proverbial candy store, and I like it and I enjoy it." According to a CBS advertisement, the network received the most accolades for its coverage of the Democratic convention.

The Republican convention was “professionally mounted, swiftly paced, and carefully timed to assure prime-time exposure.” A former television producer ran the show with stopwatch precision, according to a “secret” fifty-page script. Dan Rather obtained a copy and read from it; a passage in which representative and convention chairman Gerald Ford (R-Mich.) was to speak for one minute, from 8:53-8:54. Competing for the attention of the media were thousands of protestors against the Vietnam ar; street demonstrations led to mass arrests.

Despite low ratings, both CBS and NBC announced that they were still planning on offering gavel-to-gavel coverage in 1976. The format was not without its problem, however, especially when, in the case of the Republican convention, there was no element of surprise and networks had long dull stretches during the 3 days. ABC News chose, out of financial reasons, to do half-hour wrap-ups at 4 p.m. and a selective, edited coverage of 90 minutes in prime time.

During the general election campaign in the fall of 1972, CBS regularly organized roundtable with its four correspondents assigned to cover the Presidential candidates: Robert Pierpoint and Dan Rather who cover President Nixon, Bruce Morton and Bob Schieffer, traveling with McGovern. In early November 1972, the extensive CBS News Election Book provided anyone involved in the election night coverage background information on everything from a biography of the candidates and the major issues, a summary by Dan Rather of both camps’ campaigns, the rise of minor party, and Nixon’s scandals, which did not seem to affect his campaign.

Cronkite anchored the CBS coverage with John Hart, Dan Rather, Mike Wallace, Roger Mudd, and Eric Severeid.

|

George H. W. Bush inauguration, January 20, 1989. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On November 8, 1988, Democrat Michael Dukakis was defeated by Republican George H. W. Bush, the first incumbent vice president of the United States to win a presidential election in 152 years, since Martin Van Buren in 1836.

The 1988 election featured an open primary for both major parties, as President Reagan had served his two terms and was leaving office. On the Republican side, Reagan's vice president, George H. W. Bush, was the nominal front-runner, but he suffered from a reputation as a “wimp” and faced challenges from both Senator Dole and the Reverend Pat Robertson. His victories in the “Super Tuesday” contests guaranteed his nomination at the Republican convention at the Superdome in New Orleans from August 15 to 18, 1988. The only point of contention during the convention was his choice of the young and inexperienced Indiana senator Dan Quayle as his running mate, a decision that was widely criticized.

On the Democratic side, a long list of Democrats competed, derisively referred to as “The Seven Dwarfs”: former Arizona governor Bruce Babbitt, Delaware seantor Joe Biden, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis, Missouri representative Richard Gephardt, Tennessee senator Al Gore, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, and Illinois senator Paul Simon. The race narrowed down to Gore, Jackson, and Dukakis, who after finishing first in the New York primaries, secured the nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Atlanta, Georgia, from July 18 to 21. Jesse Jackson, who had finished second, made a behind-the-scenes effort to claim the vice presidency. He relented, however, fearful of splitting the party along racial lines, and managed to include a few planks favorable to minorities in the party platform. Dukakis instead chose Texas senator Lloyd Bentsen as his running mate, and as the successful convention ended, Democrats stood 17 percentage points ahead of Bush in the polls.

Without a clear vision and path for his own presidency, Bush campaigned against his opponent’s weaknesses, instead of stressing his qualifications for the job and his plans for the country. His speeches and campaign advertising did not address national concerns, such as the federal deficit, but focused instead on issues such as a Massachusetts prison furlough plan and Dukakis’s veto of a state law requiring public school students to recite the Pledge of Allegiance. The Bush campaign depicted Dukakis as an unreasonably left-wing liberal and a member of the ACLU. Although criticized, the plan worked, and Bush took the lead in the polls by the end of the summer and never lost it. Bush capitalized on a good economy, a stable international stage, Reagan's popularity, and emphasized Dukakis’s weaknesses. The Democratic campaign was unable to counter a series of highly effective attacks by the Bush team—most notably the famous “Tank Ride” ad—and Dukakis himself was not a very effective campaigner. Although he enjoyed a minor rebound after his vigorous performance in the first of two televised presidential debates, Dukakis lost many potential voters after the second debate. Asked by moderator Bernard Shaw whether he would still oppose capital punishment if his wife were raped and murdered, the Democratic candidate delivered an emotionless response ("I think you know that I've opposed the death penalty during all of my life”) and did not mention his wife’s name once. This did not resonate with voters, and his poll numbers dropped seven points that night, placing the governor as far as seventeen points behind. Dukakis did not give up and began drawing enthusiastic crowds in the final weeks of the campaign, even coming close to Bush in the polls in the last weeks of the campaign.

But it was too late, and George H. W. Bush won 54 percent of the popular vote and a 426–111 margin in the electoral college. It was the third presidential election Republicans won in a row, and Bush became the first incumbent vice president of the United States to win a presidential election in 152 years since Martin Van Buren in 1836. Just like Van Buren in 1840, President Bush also was defeated for reelection after serving a single term.

The campaign was extremely negative, leaving many voters disenchanted with the whole election. In his inaugural address, President Bush reached out to those who had voted against him and declared that "When I said I wanted a kinder and gentler nation, I meant it—and I mean it," he said. "My hand is out to you, and I want to be your president, too."

Television Coverage

The start of the primary season in early 1988 was not met with a lot of enthusiasm, except among journalists, who lavished a monumental amount of attention on the Iowa caucuses and on New Hampshire, where the first presidential primary was held on February 6. Covering both events, Rather was, according to the Washington Post, “determined to inject pizazz into proceedings many regard as stubbornly tedious.” He “exploded onto the air with jargon blazing,” and his “folksy, frisky rat-a-tat [was] infectious.” Faced with a lack of audience and the competition of the Winter Olympics, the three networks cut back on their coverage ahead of Super Tuesday, March 8, when twenty states and Guam elected 2,110 delegates. On the Democratic side, the major surprise of the 1988 primaries was the surge of Jesse Jackson, who won in Michigan. While he had done well in the 1984 election, Jackson was now a “plausible” nominee. But with his success came increased scrutiny by the press. Journalists pointed to weaknesses in his program, albeit always very carefully as they feared being labeled as racists. Jackson came second to Michael Dukakis and many expected, or wished, for some tension between the two men at the Democratic convention in Atlanta in July.

The DNC demonstrated how the relationship between political committees and television had reached a new level. After being warned that local stations would go back to their more lucrative programs at 11 p.m., the Democratic Party in Atlanta scheduled all convention business for prime time, 8–11 p.m. It structured the convention so that it would be “effective on television” and would serve as a positive showcase for the party. A combined telephone, computer, satellite, and print communication system was also set up, enabling the DNC to deliver news of the convention directly to televisions around the country at no charge to the stations. The party could thus secure coverage and control the image and message. With C-SPAN and CNN covering the entire convention and hundreds of local stations doing their own coverage, the three networks completely abandoned the gavel-to-gavel approach, staying instead on the convention from 9–11 on the four days. This move by the networks was a response to changes in party procedures that changed the nature of the convention, since the primaries already designated a nominee, in addition to the lack of interest by the audience for conventions, as well as a consequence of the downsizing of news divisions following new ownership. In addition, labor-saving devices enabled ABC, CBS, and NBC to cut by a third to a half the crew sent to cover the conventions, and the cost of that coverage. There were still 15,000 journalists from around the globe covering 5,400 delegates at the DNC.